Fast, private email hosting for you or your business. Try Fastmail free for up to 30 days.

Microsoft Scraps Diversity Report and Performance Review ‘Impact’ ⚙︎

Tom Warren, The Verge:

Microsoft has been publishing data about the gender, race, and ethnic breakdown of its employees for more than a decade. Since 2019 it’s been publishing a full diversity and inclusion report annually, and at the same time made reporting on diversity a requirement for employee performance reviews.

Now it’s scrapping its diversity report and dropping diversity and inclusion as a companywide core priority for performance reviews, just months after President Donald Trump issued an executive order to try and eradicate workforce diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

This won’t come as a surprise. Microsoft cut a major diversity team last year, and ongoing pressure from the Trump regime gives these companies all the cover they need to kill programs they never truly cared about. As I wrote last summer:

It was always just lip service. Companies never really bought into the progressive ideals. They just wanted to shut up Black folk.

Warren again:

Microsoft employees always had to answer “What impact did your actions have in contributing to a more diverse and inclusive Microsoft?” and “What impact did your actions have in contributing to a more secure Microsoft?” Both of these questions have been removed, replaced with a simplified form that asks employees to reflect on the results they delivered and how they achieved them, and any recent setbacks and goals for the future.

I doubt the diversity question mattered; most people likely had little useful to say. Apple added similar questions about diversity impact to its employee self-reviews a few years back (they’re still there, I’m told). I was always tempted to answer “How did you contribute to Apple’s diversity efforts?” by writing I exist—as the only Black engineering manager in the organization—but I resisted.

(Fortunately, co-chairing Black@Apple, recruiting and hiring female and Black engineers, and mentoring hundreds of employees gave me plenty to write about.)

Lisa Jackson, Kate Adams to Retire from Apple, Jennifer Newstead to Join as General Counsel ⚙︎

It’s been quite the week for Apple personnel changes. Apple Newsroom:

Apple today announced that Jennifer Newstead will become Apple’s general counsel on March 1, 2026, following a transition of duties from Kate Adams, who has served as Apple’s general counsel since 2017. She will join Apple as senior vice president in January, reporting to CEO Tim Cook and serving on Apple’s executive team.

In addition, Lisa Jackson, vice president for Environment, Policy, and Social Initiatives, will retire in late January 2026. The Government Affairs organization will transition to Adams, who will oversee the team until her retirement late next year, after which it will be led by Newstead. Newstead’s title will become senior vice president, General Counsel and Government Affairs, reflecting the combining of the two organizations. The Environment and Social Initiatives teams will report to Apple chief operating officer Sabih Khan.

Newstead joins Apple from Meta, where she was the chief legal officer. Quite the executive exchange. I’ll bet Apple got the better end of the bargain.

With this string of departures, perhaps Tim Cook actually is planning a near-term exit and these retirements are all about clearing the decks so it won’t seem like they’re bailing on the new guy.

No doubt Adams will be missed, but on a personal level, it’s Lisa Jackson’s departure that I think is most relevant and impactful.

I was deeply fortunate to have worked with her while I was co-chair for Apple’s African-American Employee Association/Black@Apple group (what Apple calls “Diversity Network Associations” or DNAs), and she was the DNA’s “executive sponsor.” Jackson was always extremely supportive of our efforts to build community among our Black employees and to host meaningful conversations that emphasized the cultural impact of Black contributions to society. It was through her efforts that we hosted such luminaries as Congressman John Lewis, Bryan Stevenson, Floyd Norman, and Carla Harris.

I understand moving her Environment team under Sabih Khan, Apple’s COO—it’s directly tied to Apple’s bottom line—but it troubles me that her Social Initiatives team will also move under Khan. For instance, I can’t help but wonder what will become of the Racial Equity and Justice Initiative (REJI) she championed and led. Social Initiatives aren’t an “operational” issue, simply one more set of dials to turn to make Apple more efficient or profitable. With ongoing pressure from the Trump administration to abandon diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives (which other tech companies like Microsoft seem happy to do), I worry that with Jackson’s departure, Apple could be the next to end its diversity and inclusion practices. No doubt her leadership here will be missed.

Claude the Albino Alligator Dies at 30 ⚙︎

California Academy of Sciences:

It is with a heavy heart that we share the news that Claude, our beloved albino alligator, has passed away at the age of 30. Claude was an iconic California Academy of Sciences resident who many visitors formed deep connections with during his 17 year tenure. He brought joy to millions of people at the museum and across the world, his quiet charisma captivating the hearts of fans of all ages. Claude showed us the power of ambassador animals to connect people to nature and stoke curiosity to learn more about the world around us.

The team later determined that Claude had “extensive liver cancer with evidence of liver failure” and that “[t]reatment options were limited and likely would have had minimal success.”

“Fuck cancer” is always the appropriate response—human or reptile.

Also: George Kelly’s obituary in The San Francisco Standard.

I visited Claude several times after he moved in. Here he is in August 2014, a month before his 19th hatchday:

I’ll admit I always harbored an irrational fear of Claude whenever I visited, worried he’d pick that day to finally scale the rocky walls of his swamp seeking food fresher than frozen fish.

Fortunately, Claude was always too chill to chase.

Later, gator.

The British Public: Die Hard Is Not a Christmas Movie ⚙︎

Nadia Khomami, reporting for The Guardian on a UK poll:

The survey of 2,000 people by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) found that 44% did not believe Die Hard to be a Christmas film.

Alan Dye Departs Apple for Meta, Design Vet Steve Lemay Takes Over ⚙︎

Mark Gurman, Bloomberg (paywalled; Reuters, Archive.today):

Meta Platforms Inc. has poached Apple Inc.’s most prominent design executive in a major coup that underscores a push by the social networking giant into AI-equipped consumer devices.

The company is hiring Alan Dye, who has served as the head of Apple’s user interface design team since 2015, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Apple is replacing Dye with longtime designer Stephen Lemay, according to the people, who asked not to be identified because the personnel changes haven’t been announced.

Apple confirmed the move in a statement provided to Bloomberg News.

Gurman calls this “a blockbuster coup” for Meta and a “big loss for Apple,” but I think he got his order wrong—Apple is probably happy to finally wave bye-bye, Dye.

Dye comes from the world of glossy print, packaging, and brand marketing, and was initially hired onto Apple’s Marcom (Marketing Communications) team to work on iPod and iTunes marketing. When he moved to the UI team for the iOS 7 redesign, several coworkers expressed concerns that a “marketing guy” was designing the UI.

I think Meta is getting exactly who they deserve.

Steve Lemay is taking over Dye’s role:

“Steve Lemay has played a key role in the design of every major Apple interface since 1999,” Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook said in the statement. “He has always set an extraordinarily high bar for excellence and embodies Apple’s culture of collaboration and creativity.”

One former colleague who worked with Lemay found him less than helpful as a designer and expressed surprise he’d managed to achieve such a senior design role, but Lemay at least seems to have a deep background in UI design. I hope that translates to Liquid Glass improvements.

One final note: Gurman’s reporting includes this nugget:

The executive informed Apple this week that he’d decided to leave, though top management had already been bracing for his departure, the people said.

Jeff Williams’ departure announcement noted that the Design team, headed by Dye, was to move under Tim Cook. I wrote then:

Reporting to Cook is a hell of an elevation for Dye […].

I presume this reporting structure is temporary, a stopgap until they find something—someone—better. Cook has enough problems on his plate. I can’t imagine him caring enough about design to push back on bad or poorly implemented ideas […].

(A little birdie informed me that after Jony Ive left, Dye refused to report to Federighi—who apparently has strong opinions on UI design—which is how Williams ended up with the group. I’m curious if reporting to Cook is an extension of that refusal.)

My presumption was Dye would eventually report to someone other than Cook.

Williams leaves in mid-November, Dye starts reporting to Cook, and two weeks later, Dye is gone.

Did Cook again try to move Design under Federighi (where I think it belongs) or under John Ternus (to give him broader experience before he ascends), and did Dye again refuse? Or did Cook and Dye not get along?

Perhaps Apple wasn’t so much “bracing” for his departure as eagerly anticipating it.

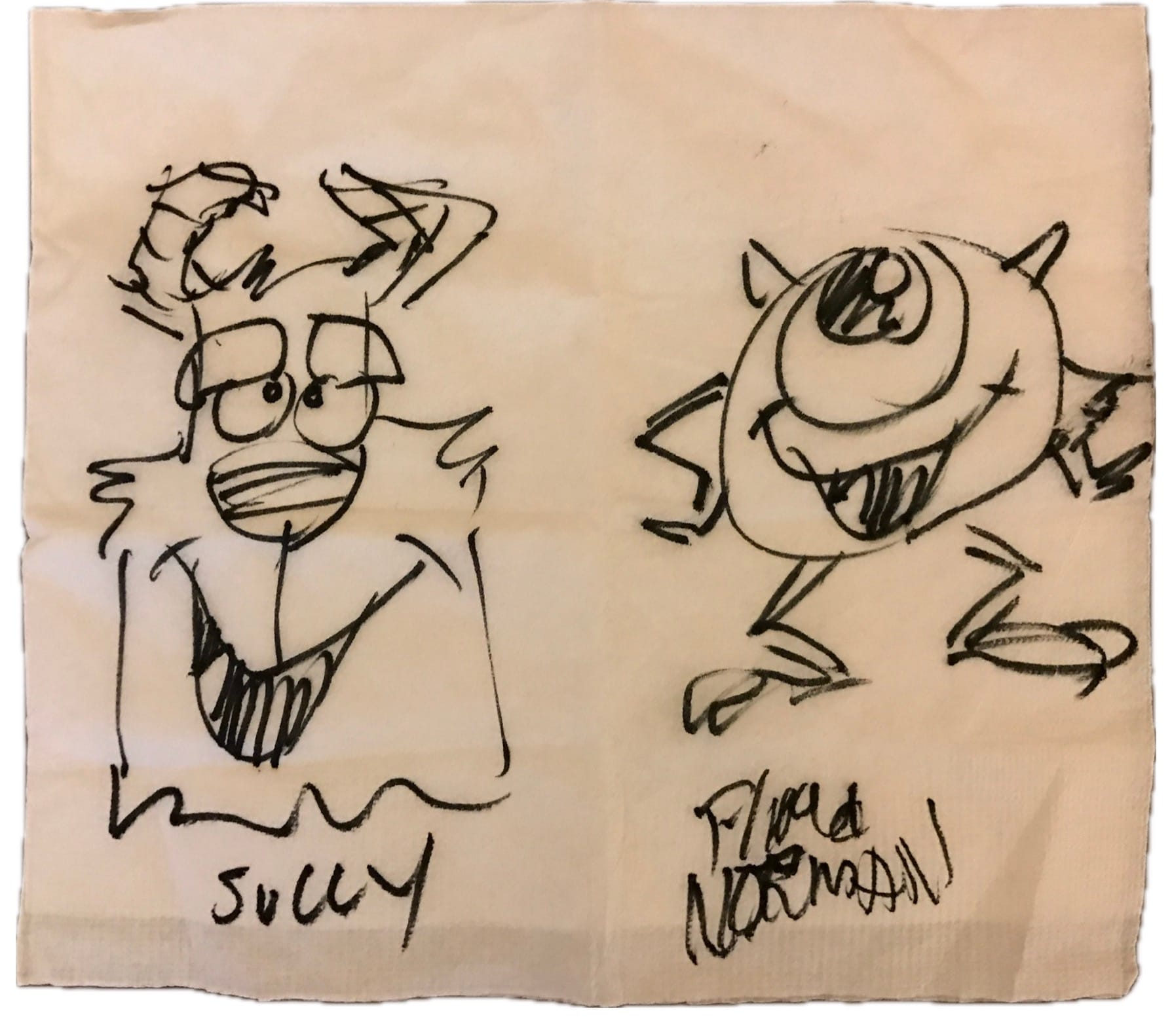

‘Floyd Norman: An Animated Life’ Chronicles the Career of Disney’s First Black Animator

Floyd Norman is the first African-American animator at Disney, and the subject of a terrific and heartwarming—though at times infuriating—2016 documentary, Floyd Norman: An Animated Life, which chronicles his long career in animation, his forced retirement from Disney at age 65, and why he persisted in showing up at the studio anyway.

While at Disney, Norman’s work included Sleeping Beauty, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and The Jungle Book. He also worked on some of my favorite early cartoons at Hanna-Barbera (Josie and the Pussycats, Jabberjaw, Laff-A-Lympics, and The Smurfs, to start) and at Pixar on some of their most memorable films (Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc., and others).

Apple’s African-American Employee Association (AAEA) held a special screening for the film shortly after its release. I was co-chair of AAEA then (with my good friend Ron Lue-Sang), and we, along with several other members, were fortunate enough to meet Norman and a few folks from the film’s creative team. He was brimming with boyish charm, with a devilish gleam and a delightful impishness. I found myself a giddy kid in his presence.

While chatting over dinner with Ron and me, Norman quickly sketched Sully and Mike from Monsters, Inc. on a napkin. I may have squealed. It was clear he still loved his work—both creating the art and seeing the joy it brings. I’m guessing that’s just as true today as it was nearly a decade ago.

That screening remains one of my favorite events I was lucky enough to host at Apple, and the film remains one of my favorite documentaries. You will be captivated by Norman’s enthusiasm and verve.

Floyd Norman: An Animated Life is available on HBO Max and The Criterion Channel.

John Giannandrea Leaving Apple ⚙︎

Apple today announced John Giannandrea, Apple’s senior vice president for Machine Learning and AI Strategy, is stepping down from his position and will serve as an advisor to the company before retiring in the spring of 2026. Apple also announced that renowned AI researcher Amar Subramanya has joined Apple as vice president of AI, reporting to Craig Federighi. Subramanya will be leading critical areas, including Apple Foundation Models, ML research, and AI Safety and Evaluation. The balance of Giannandrea’s organization will shift to Sabih Khan and Eddy Cue to align closer with similar organizations.

JG’s departure comes as a surprise to absolutely no one after he was effectively sidelined by Tim Cook following the delay of the “more personalized Siri” features, which relied heavily on Apple Intelligence—the rollout of which has been less than stellar. Apple is positioning this as his “retiring,” but JG has long been a man without a portfolio. I’m surprised only that it’s taken this long.

JG was seemingly too focused on research and development and not enough on shipping products (in Apple terms, he was perhaps good at his “Category 1”—AI research—and not so great at his “Category 3”—making that work available for others to successfully perform their Category 1).

Breaking up JG’s organization makes sense, then. (My understanding is it was a mess—apparently the admin he brought over with him from Google was running the team.) Subramanya keeps JG’s research and foundational AI portfolio (under Federighi’s SWE—Software Engineering), while I’ll guess that AI infrastructure, which wouldn’t fit well under SWE, shifts to Khan (Apple’s COO), and front-end and related services lands with Cue, who owns Services (like the App Store and App Store Connect). Fortunately, Cue’s and Federighi’s teams have a lot of experience working together to deliver products (Xcode Cloud or In App Purchase are but two examples), so I’m confident this bodes well for the future of Apple Intelligence.

I don’t know Subramanya (I suppose he’s “renowned” among AI researchers?). He left Microsoft after only five months to join Apple, after spending 16 years at Google (twice that of Giannandrea). Is another long-time Google executive the right move here? If he’s willing to leave Microsoft after just five months, what happens when Meta or OpenAI come calling with a yet-better offer? On the other hand, if Apple does partner with Google to use Gemini, having someone with deep familiarity of that team could prove valuable. I’m cautiously optimistic here.

(Amusingly, Subramanya’s LinkedIn still shows his last post, where he is “super excited” to start at Microsoft and was “feeling deeply energized” a week in, describing Microsoft’s culture as “refreshingly low ego yet bursting with ambition.” Either something changed or Apple made a really great offer.)

Intel Rumored to Fab Apple’s Lowest-End M-Class Chips (Not Intel’s) ⚙︎

Kai Nicol-Schwarz at CNBC, summarizing an X/Twitter post from analyst Ming-Chi Kuo:

The partnership would see Intel shipping its lowest-end M processor to Apple as early as second or third quarter 2027.

And:

Shares in Intel rose 10% on Friday after TF International Securities analyst Ming-Chi Kuo posted on X that he expected Intel to begin shipping its lowest-end M processor to Apple as early as second or third quarter 2027.

I can’t tell if Nicol-Schwarz’s use of “its” following “Intel” is hasty and unclear writing, or a misunderstanding of who “owns” the M-series processors.

Here’s the first line of Kuo’s X/Twitter post:

Intel expected to begin shipping Apple’s lowest-end M processor as early as 2027.

Later, Kuo writes:

Apple’s plan is for Intel to begin shipping its lowest-end M processor […]

My guess is this is where Nicol-Schwarz got things wrong, misinterpreting “its” here to refer to Intel rather than to Apple, despite the clear (to me) antecedent.

These are Apple’s M-class processors, not Intel’s. The M-series (M1 through M5) is created by Apple. They design them in-house, then have a chip manufacturer (currently TSMC) build (fabricate, or “fab”) them to Apple’s specifications. The supposed deal would have a small portion of those chips fabbed by Intel instead of TSMC.

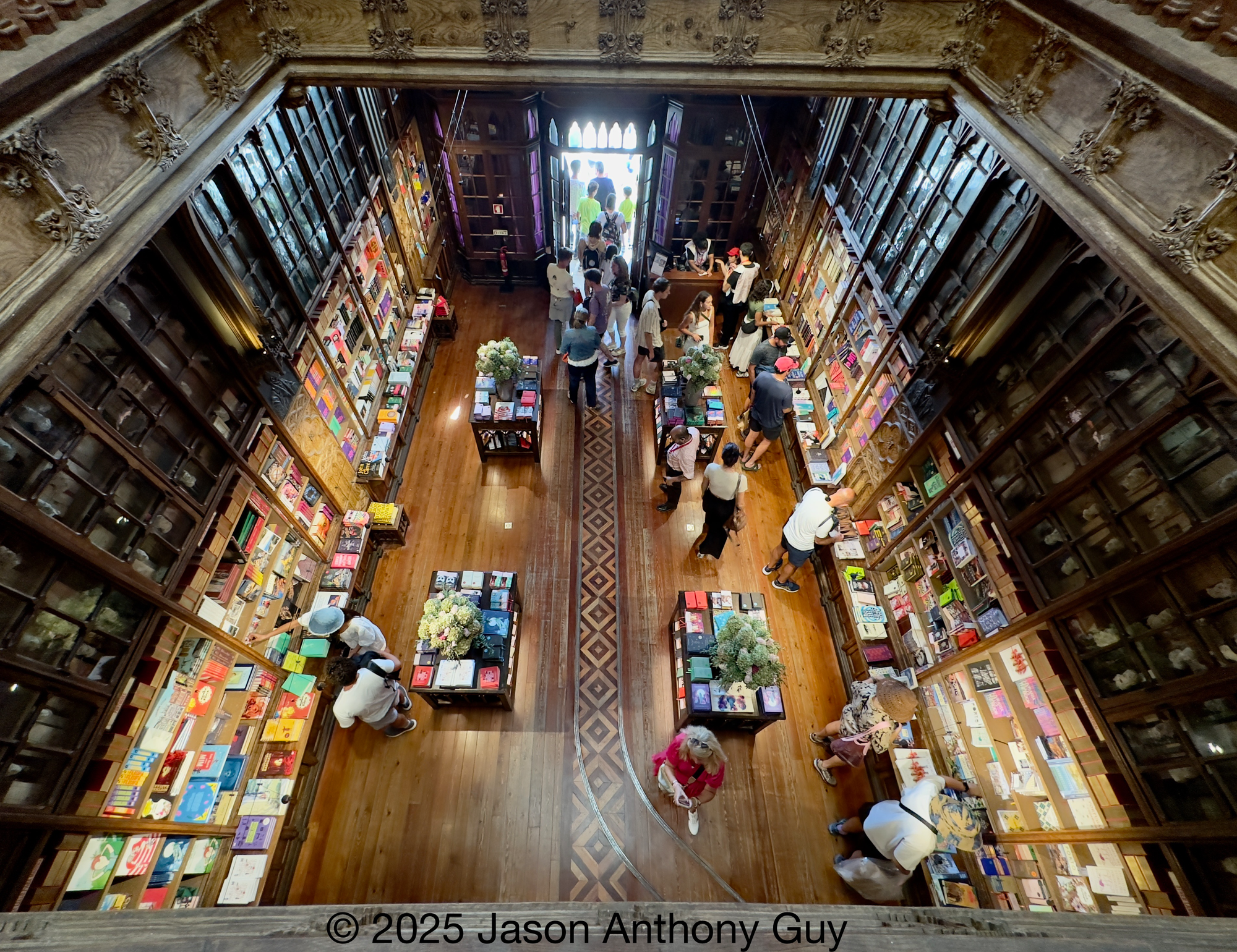

Silent Sunday

Posted on Mastodon under #SilentSunday, #Photography.

Tom Stoppard Dies at 88 ⚙︎

Bruce Weber, with unhappy news in The New York Times (gift link):

Tom Stoppard, the Czech-born English playwright who entwined erudition with imagination, verbal pyrotechnics with arch cleverness, and philosophical probing with heartache and lust in stage works that won accolades and awards on both sides of Atlantic, earning critical comparisons to Shakespeare and Shaw, has died at his home in Dorset, England. He was 88. […]

Few writers for the stage — or the page, for that matter — have exhibited the rhetorical dazzle of Mr. Stoppard, or been as dauntless in plumbing the depths of intellect for conflict and drama. Beginning in 1966 with his witty twist on “Hamlet” — “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” — he soon earned a reputation as the most cerebral of contemporary English-language playwrights, venturing into vast fields of scholarly inquiry — theology, political theory, the relationship of mind and body, the nature of creativity, the purpose of art — and spreading his work across the centuries and continents.

Tom Stoppard has been an essential part of my theatrical and movie-going upbringing for nigh on forty years. I first encountered his work in the late 1980s, shortly after I joined the New York Parks’ Shakespeare Company to study acting. We were learning Hamlet and our directors shared Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead as a way of fleshing out our understanding of the story, an alternate view into the play that highlighted the absurdities of Shakespeare’s tragedy.

I loved it. It tickled my brain in exactly the right way.

Unsurprisingly, I was equally smitten by Shakespeare in Love, the screenplay for which Stoppard won an Oscar and Golden Globe. It remains one of my favorite movies (and only in small part due to Gwyneth Paltrow).

I first saw Arcadia in 2004, and again in 2013. In between, I saw The Real Thing, Travesties, Rock ’n’ Roll, and Indian Ink: Stoppard was in regular rotation at San Francisco’s A.C.T., for which I’m terribly grateful.

Until today, I wasn’t aware that he was an often-uncredited script doctor, punching up movies, from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade to Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. I shouldn’t be surprised: Last Crusade is my favorite of that trilogy, and RotS is considered the best of the Star Wars prequel entries.

I loved Stoppard’s faculty with language, his playfulness, his ability to go from farcical to philosophical in a single phrase. His “exit is an entrance somewhere else.” Like other timeless, surname-is-sufficient writers—Shakespeare, Shaw, Beckett—Stoppard leaves us with his breathtakingly exquisite words.

“Words, words. They’re all we have to go on.”

David Lerner, Co-Founder of Tekserve, Dies at 72 ⚙︎

Sam Roberts at The New York Times (gift link), reporting heartbreaking news:

David Lerner, a high school dropout and self-taught computer geek whose funky foothold in New York’s Flatiron district, Tekserve, was for decades a beloved discount mecca for Apple customers desperate to retrieve lost data and repair frozen hard drives, died on Nov. 12 at a hospital in Manhattan. He was 72.

The cause was complications of lung cancer, said his wife, Lorren Erstad, his only immediate survivor.

Truly, Fuck. Cancer.

Tekserve was a tremendously welcoming space, filled with wonder and delight. When the store closed in 2016 I wrote on Twitter:

🙁 always loved Tekserve. Was my go-to store for years.

In the late-’80s and well into the ’90s, I would often visit just to see what new hardware and software had been released and to chat to other Mac users. It didn’t feel like there were a lot of us back then, but the lot of us loved Tekserve. Lerner (and his co-founder Dick Demenus) built a community in the shape of a store.

RIP.

Thanksgiving Leftover Recipes ⚙︎

New York Times Cooking:

Thanksgiving leftovers are arguably the best part of the holiday. Make the most of them with our wonderful recipes for the ideal turkey sandwich, potpie, tetrazzini, soups and more.

If Open-Faced Hot Turkey Sandwiches or Turkey and Apple Sandwiches With Maple Mayonnaise are still too on-the-nose, perhaps Turkey Pho, Potato Scones, Thanksgiving Leftovers Hot Pockets, or Birria de Pavo would be more pleasing to the palate.

Certainly more palatable than my last link.

(Recipe gift links.)

The Sordid Tale of Olivia Nuzzi, RFK Jr., and Ryan Lizza ⚙︎

Brian Phillips, at The Ringer, brings us a story I never expected to be linking to the day after Thanksgiving, but better now than yesterday. It’s salacious and sickening in equal measure. Too juicy to ignore, and yet I wish I’d never learned of it:

There’s no way around it. If you read this article, you are going to have to imagine Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the United States secretary of health and human services, having an absolutely eyeball-melting orgasm. You’re going to have to imagine a sweaty, leathery man in his early 70s, the scion of the celebrated Kennedy political dynasty, bellowing like a Spartan as his body yields to the sweet, sweet release. Knees buckling. Sinews straining. What does it sound like when RFK Jr. bellows? I’ll go out on a limb and say it’s gritty. His normal speaking voice is basically a garbage disposal. When the big one hits, it must be like tossing a fork in.

[…]

But hang on. Do you have any idea what I’m talking about? Have you been following this scandal at all? My sense is that of the people reading this, half will have no idea who Olivia Nuzzi and Ryan Lizza are, while the other half—sickos and journalists, but I repeat myself—have been bingeing the story for months and keep all the details on murderboards in their brains.

If you’re just joining us, welcome. Let’s take a minute to get you up to speed.

I’m aware of this story primarily because Keith Olbermann, who dated Nuzzi when she was 19 and he was 50-something, gleefully shares regular, snarky updates on his Countdown podcast.

Apple’s Holiday Film, ‘A Critter Carol’ ⚙︎

Apple annual holiday film is here:

In this handcrafted film, a ragtag group of woodland critters discover a lost iPhone 17 Pro and use it to film themselves singing a song of friendship as a gift, before returning it to its rightful owner.

Shot on iPhone 17 Pro, the spot features puppets instead of people and is more whimsical than Apple’s usual tear-jerkers. It’s inspired by the Flight of the Conchords song “Friends,” maintaining much of the original’s quirkiness while avoiding some of the more, uh, colorful lyrics.

Also: The Making Of… video, which is equally delightful.

Franklin: The Legacy of Peanuts’ First Black Character ⚙︎

I very much enjoyed the Minnesota Historical Society’s in-depth panel discussion of the legacy of Peanuts’ Franklin, featuring Robb Armstrong, the creator of the long-running Jump Start comic strip, one of the screenplay writers for the aforelinked Welcome Home, Franklin, and the person whose surname Charles Schulz chose for Franklin. Armstrong’s a great storyteller, and his own history of becoming a cartoonist and his relationship with Schulz is deeply moving.

How Franklin Joined ‘Peanuts’ ⚙︎

Happy Thanksgiving! As we Americans celebrate the holiday by devouring turkey and watching A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving (as is tradition), I recommend also watching Welcome Home, Franklin, the in-world backstory of how Franklin Armstrong joined the Peanuts family. Plus, catch the real-life story of how retired teacher Harriet Glickman convinced Peanuts creator Charles Schulz to add his first Black character—Franklin—to his comic strip after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968.

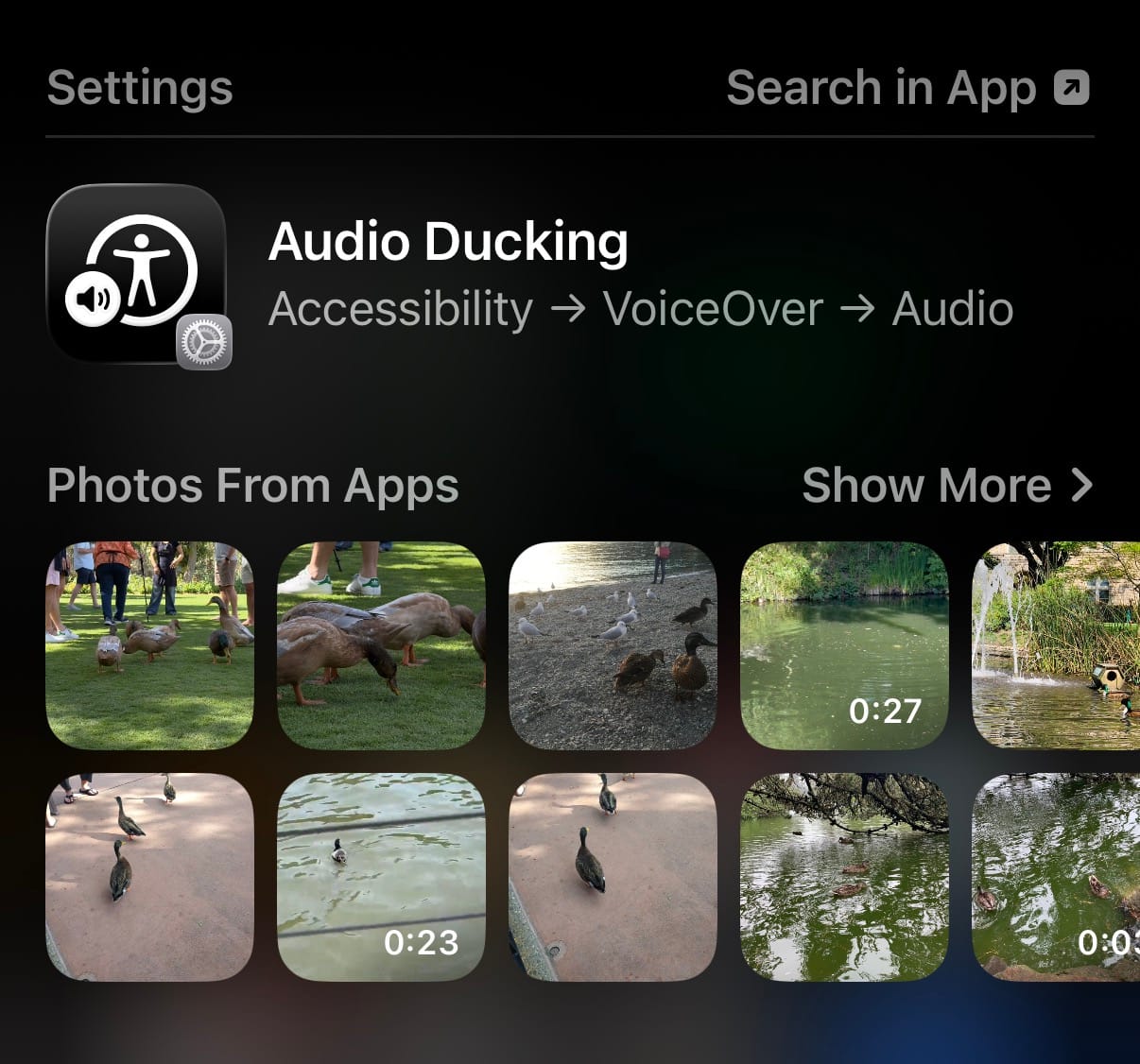

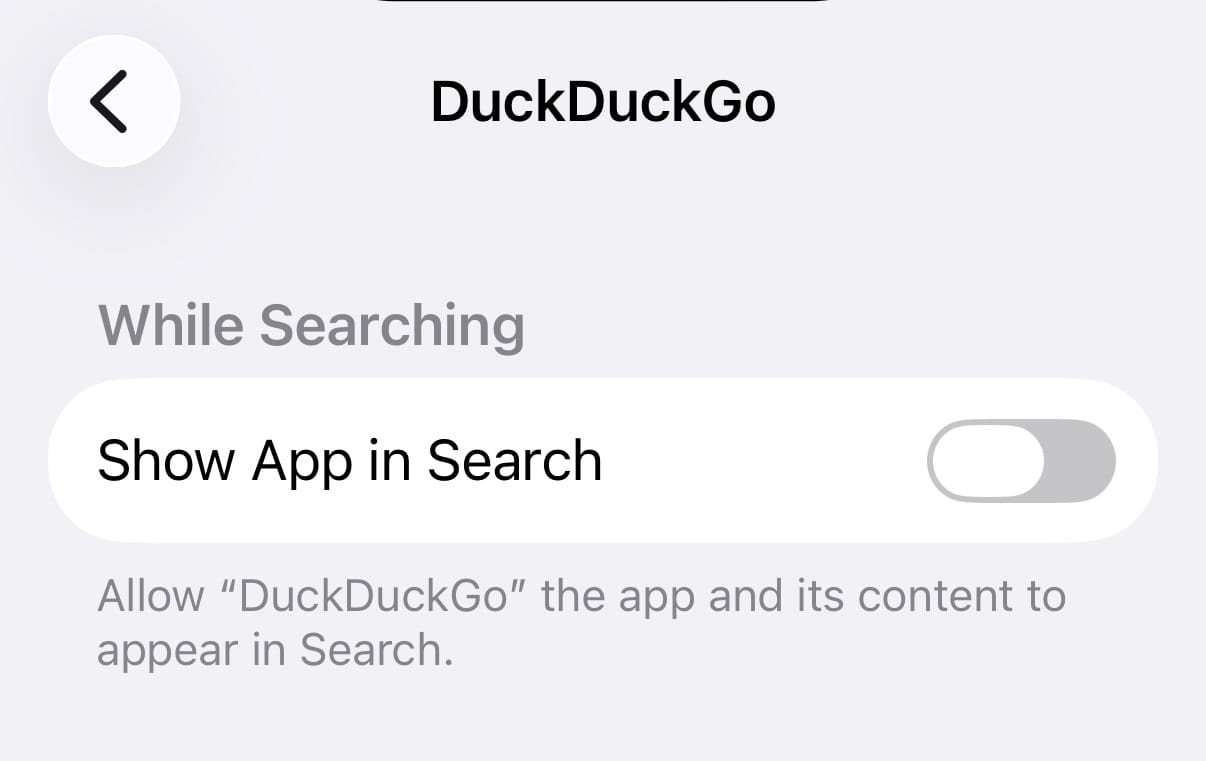

Easy but Unexpected Fix for Apps Not Appearing in iOS Spotlight Searches

This is one of those silly yet annoying things that drives me batty.

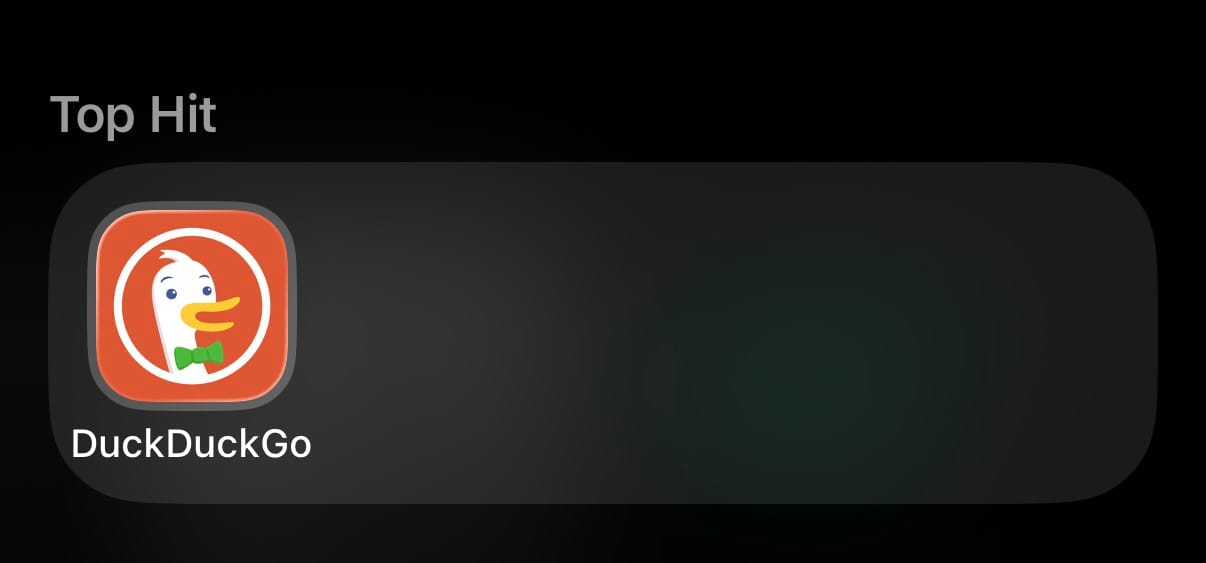

A few days ago, I tried using Spotlight search on iOS to open the DuckDuckGo web browser. Normally I swipe down on the Home Screen and type “duck,” but instead of showing the app, it returned a link to the website, Siri Knowledge about the DuckDuckGo company, the Audio Ducking setting, and dozens of photos of ducks I’d forgotten I’d taken.

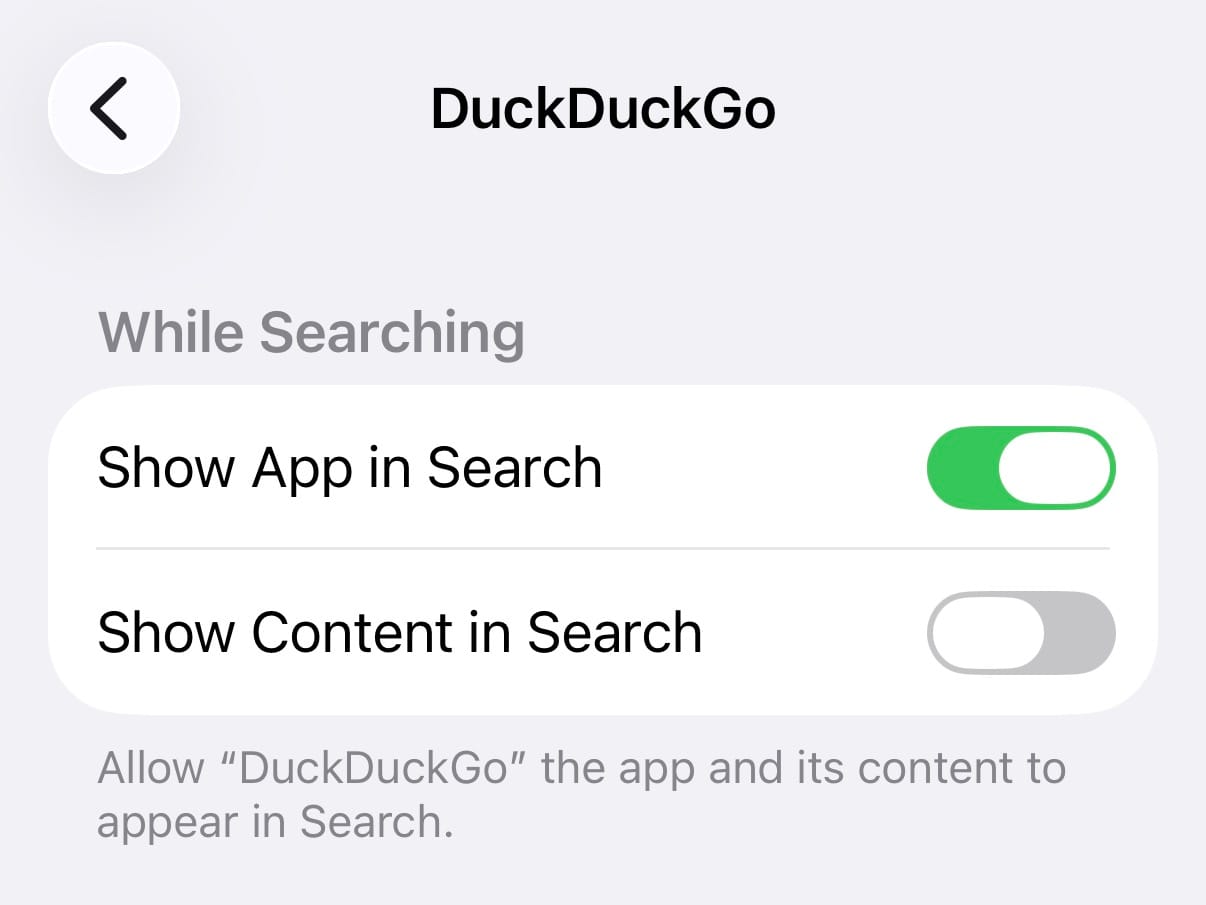

After several minutes of troubleshooting the issue (including restarting my device), I stumbled across the cause: at some point I’d unknowingly disabled the Settings > Search > Show App in Search option for DuckDuckGo.

I don’t recall doing so. This was a new iPhone, just a few weeks old, set up by transferring all data and settings from my previous iPhone. The old phone had the setting enabled. Upon (re-)enabling it on the newer device, my Spotlight search worked again.

(This is not a setting that gets synced between devices, from what I’ve determined, so either I actually changed it and forgot, or it “got changed” from under me by the system. The former is infinitely more likely, but I’m not completely ruling out the latter.)

Frustratingly, there’s no easy way to check whether any given app has this setting disabled without tapping into each app under Settings > Search, a vexing task for anyone with more than a handful of apps, and an overwhelming chore for someone with let’s see… 692 apps installed.

(I’d appreciate an option to scroll through a list of apps that have this setting disabled, and to reset all apps so they show in search. For my Apple friends: FB21172336, Need easier way to see which apps have “Show App in Search” disabled.)

If you’re using Spotlight search and wondering why an app you know is on your system isn’t showing up, check whether Show App in Search was disabled for it.

Hopefully, this helps someone else who was pulling out their hair.

White House Can’t Handle the Truth About Illegal Orders ⚙︎

Malcolm Ferguson, The New Republic:

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt says “all orders” from President Trump are “lawful orders,” and troops have no right to question him.

“All lawful—all orders—lawful orders are presumed to be legal by our service members. You can’t have a functioning military if there is disorder and chaos within the ranks,” Leavitt told reporters outside the White House on Monday. “And that’s what these Democrat members were encouraging. It’s very clear. And not a single one of them since they’ve been pressed by the media … can point to a single illegal order that this administration has given down because it does not exist.

“You can’t have a soldier out on the battlefield or conducting a classified order questioning whether that order is lawful or whether they should follow through,” Leavitt argued earlier, in a twisted reading of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

If those members of Congress had said “you can refuse to eat poisoned food,” Leavitt would insist “all food from this White House is presumed to be safe and no one can point to a single poisoned meal from this administration.”

Setting aside the reality that military members are legally and morally obligated to refuse illegal orders, this regime is telling on itself by taking a factual statement about defying illegal orders and insisting it’s about defying legal orders. To declare that these congresspeople said the opposite of what they did—and to further assert that every order from the president is legal—is disturbingly Orwellian, even for a regime that revels in doublethink. There’s clear consciousness of guilt in their over-the-top protestations.

‘Trump Is Losing Control of Himself’ ⚙︎

Tom Nichols, The Atlantic (gift link; Apple News+):

Yesterday, Trump seemed to lose the last bit of his grip on his emotions as he fired off a fusillade of Truth Social posts. (“Trump must not have slept well Wednesday night,” Bill Kristol and Andrew Egger of The Bulwark observed today.) “This is really bad,” the president wrote, “and Dangerous to our Country. Their words cannot be allowed to stand. SEDITIOUS BEHAVIOR FROM TRAITORS!!! LOCK THEM UP???”

[…]

[Press Secretary Karoline] Leavitt then tried to turn the entire ghastly business on its head. “Many in this room want to talk about the president’s response, but not what brought the president to responding in this way,” she said—as though members of Congress publicly speaking their minds somehow justified the death threats.

Jimmy Cliff, Reggae Legend, Dies at 81 ⚙︎

Alex Marshall, New York Times:

Jimmy Cliff, the Jamaican reggae singer who helped popularize the genre around the world with songs like “You Can Get It If You Really Want” and “The Harder They Come,” has died. He was 81.

Mr. Cliff’s wife, Latifa Chambers, announced his death in a post online early Monday. She said the cause was a seizure followed by pneumonia.

I suspect Jimmy Cliff is relatively unknown to American audiences (compared to, say, Bob Marley, who Cliff essentially discovered), but he’s legendary among West Indians, especially those growing up in the ’70s and ’80s. Without Cliff, it’s unlikely reggae would have achieved its level of popularity and influence.

RIP to a musical legend.

See Also: Ben Sisario’s Times companion piece, “Jimmy Cliff: 8 Essential Songs”. I consider Cliff’s version of “I Can See Clearly Now” to be the definitive cut. Not on the list, but also worthy: Brown Eyes, a lovely ditty that’s a quintessentially mid-’80s mashup of reggae, electropop, and rap, co-written by, of all people, La Toya Jackson.

Mark Gurman Throws Cold Water on Tim Cook’s Departure Timing ⚙︎

Mark Gurman, in his Power On newsletter at Bloomberg (paywalled; archive), unambiguously refutes the recent Financial Times report that Tim Cook will step down as CEO “as soon as next year”:

Based on everything I’ve learned in recent weeks, I don’t believe a departure by the middle of next year is likely. In fact, I would be shocked if Cook steps down in the time frame outlined by the FT. Some people have speculated that the story was a “test balloon” orchestrated by Apple or someone close to Cook to prepare Wall Street for a change, but that isn’t the case either. I believe the story was simply false.

In linking to the FT report, I suggested it “could be a scoop, a PR plant, or the entire piece could be based on a few people setting up a WebEx call and ordering pizza.” I didn’t consider “simply false” as an option. That’s pretty unequivocal.

Gurman also calls the FT report “premature,” with “few signs internally that he’s about to hand off the baton.”

Will FT respond?

Coast Guard Updates Then Quickly Reverses ‘Hate Symbol’ Policy on Swastikas and Nooses ⚙︎

Tara Copp and Michelle Boorstein, in a Washington Post “exclusive” on Thursday (semi-gift link; Apple News+):

The U.S. Coast Guard will no longer classify the swastika — an emblem of fascism and white supremacy inextricably linked to the murder of millions of Jews and the deaths of more than 400,000 U.S. troops who died fighting in World War II — as a hate symbol, according to a new policy that takes effect next month.

Instead, the Coast Guard will classify the Nazi-era insignia as “potentially divisive” under its new guidelines. The policy, set to take effect Dec. 15, similarly downgrades the classification of nooses and the Confederate flag, though display of the latter remains banned, according to documents reviewed by The Washington Post.

This caused an uproar, as anyone with any sensibility would expect. The only ones who believed explicitly reclassifying Nazi symbols and nooses as merely “potentially divisive” was a good idea were Nazis and racists.

By late Thursday, the Coast Guard, in what The Washington Post called “a stunning and hasty reversal,” had changed their mind and their policy. Copp and Boorstein, joined by Hari Raj and Victoria Bisset, reported the change (semi-gift link; Apple News+):

The abrupt policy change occurred hours after The Washington Post first reported that the service was about to enact new harassment guidelines that downgraded the meaning of such symbols of fascism and racism, labeling them instead “potentially divisive.” That shift had been set to take effect Dec. 15.

In a memo to Coast Guard personnel, the service’s acting commandant, Adm. Kevin Lunday, said the policy document issued late Thursday night supersedes all previous guidance on the issue.

“Divisive or hate symbols and flags are prohibited,” Lunday wrote in his memo. “These symbols and flags include, but are not limited to, the following: a noose, a swastika, and any symbols or flags co-opted or adopted by hate-based groups as representations of supremacy, racial or religious intolerance, anti-semitism, or any other improper bias.”

Public outrage works.

With this regime, it’s all-too-easy to believe the worst: that the first revision of the policy was specifically meant to soften the Coast Guard’s stance on these symbols, with the goal of allowing them when they weren’t previously allowed. I don’t believe that’s the case, here. Rather, the update reads like a typical HR bureaucratese rewrite aimed at providing as much latitude as possible when interpreting the guidelines to prevent unintended consequences and bad-faith (or weaponized) abuse.

Chapter 11.A.3 of the guidelines states:

A symbol or flag is divisive if its public display adversely affects good order and discipline, unit cohesion, command climate, morale, or mission effectiveness.

So an item’s “divisiveness” already depends on the effect it has.

Meanwhile, 11.B.1 notes that “a noose, a swastika,” etc. are “[p]otentially divisive symbols and flags,” and 11.C.2 notes:

Displays that exist for an unquestionably legitimate purpose should not be subject to removal. Examples include state-sanctioned items or when the symbol or flag is only an incidental or minor component, such as in works of art, or in educational or historical displays […]

My read: because swastikas and nooses may appear “in works of art, or in educational or historical displays,” they couldn’t always be classified as “divisive,” as their divisiveness depends on the context. Thus “potentially.”

The updated memorandum (correctly) redefines nooses and swastikas as “divisive or hate symbols” that are “prohibited and shall be removed.” It also eliminates the “works of art, or in educational or historical displays” carve-out (leaving it only for the Confederate battle flag). While this is much clearer, I’m confident that some historical and educational artifact will soon get flagged as a “divisive or hate symbol” and removed—and we’ll see an uproar over that.

As I said, HR bureaucratese.

Chadwick Boseman Gets Posthumous Star on ‘a Prime Spot’ on Hollywood Walk of Fame ⚙︎

Angelique Jackson, Variety:

On a starry January evening in 2018, Chadwick Boseman stepped out of a black car and onto the royal purple carpet outside the Dolby Theatre for the world premiere of his newest film, “Black Panther.” […]

“This is an epic experience,” Boseman told reporters, grinning widely as he looked out at Hollywood Blvd., blocked off for an assembly of A-listers dressed in their finest African garb. […]

Now, more than seven years later, on Nov. 20, a red carpet will be rolled out on that famed stretch of sidewalk once again as Boseman gets immortalized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Upon learning Boseman’s terrazzo and brass monument will be located near the same venue, his “Black Panther” co-star Lupita Nyong’o says reverently: “It means it won’t be missed. A place of prominence for a king.”

Bentley Maddox, E! News:

Five years after the Black Panther star died at age 43 following a battle with colon cancer, he was posthumously awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and his wife Simone Ledward-Boseman honored the late actor by bringing a piece of him to the unveiling ceremony.

During the Nov. 20 event, Simone placed a pair of Chadwick’s shoes on his newly-minted star so that he could “step” on the memorial alongside her and his brothers Derrick Boseman and Kevin Boseman.

I watched a bit of the live-streamed ceremony and it was very moving. It’s hard to believe it’s been five years. I still recall my anguish when I learned of his death. (Coincidentally, it’s the last thing I wrote about in my now-defunct personal blog.)

I always thought of Boseman as supremely talented. I remember being blown away by him as James Brown in Get on Up—he was absolutely sensational. In Marshall, he was quietly brilliant. I rewatched a 2011 episode of Castle, and he was captivating in his five minutes of screen time. Black Panther, of course, was a cultural phenomenon, but it was Boseman as T’Challa that gave that movie its heart. (Watch how fans react to him when he surprises them on The Tonight Show to understand his impact.)

He seemed like a genuinely nice, thoughtful guy. I’m heartbroken he’s not alive to accept the honor himself.

Amazon Cuts 14,000 Jobs In October, Ahead of Holiday Season ⚙︎

It would be disingenuous of me not to acknowledge Amazon’s massive layoffs, coming right as we head into the holiday season, seeing as I just posted about Amazon’s early Black Friday Apple deals.

Annie Palmer, last month for CNBC:

Amazon said Tuesday that it will lay off about 14,000 corporate employees, marking the latest cuts in the company’s multiyear effort to rein in costs.

In a blog post, the company wrote that the layoffs are being carried out to help make the company leaner and less bureaucratic, while it looks to invest in “our biggest bets” including generative artificial intelligence.

Palmer, today:

Documents filed in New York, California, New Jersey and Amazon’s home state of Washington showed that nearly 40% of the more than 4,700 job cuts in those states were engineering roles.

Amazon CEO Andy Jassy has been on a multiyear mission to transform the company’s corporate culture into one that operates like what he calls “the world’s largest startup.” He’s looked to make Amazon leaner and less bureaucratic by urging staffers to do more with less and cutting organizational bloat.

Related: There are ongoing calls to boycott Amazon (and Target and Home Depot) from November 27 (Thanksgiving) through December 1 (Cyber Monday) for “enabling” the Trump regime. From “We Ain’t Buying It”:

This action is taking direct aim at Target, for caving to this administration’s biased attacks on DEI; Home Depot, for allowing and colluding with ICE to kidnap our neighbors on their properties; and Amazon, for funding this administration to secure their own corporate tax cuts.

They’re encouraging a “full black out” on spending at those three companies during that long weekend, and urging consumers to redirect their spending to shop “small, local, or with businesses affirming our humanity.”

Apple AirTags 4-Pack Is $65 on Amazon (and Other Early Black Friday Apple Discounts) ⚙︎

Currently $99 direct from Apple. Shared by a friend inside Apple who notes the 34% discount is significantly better than Apple’s employee pricing. The single pack is 38% off ($18), but the four-pack is a better deal.

(Worth mentioning: rumors of slightly improved AirTags, which have been “coming soon” for months now.)

My friend also pointed out the A16 iPad 11” is $279 $274 at Amazon (20% 21% off, better than Apple’s “friends and family” discount), but crucially, it’s the “not ready for Apple Intelligence” model released in March, currently $349 direct from Apple, which I’ve gone on record as saying “I could not in good conscience suggest” buying “except in some very limited instances.” I stand by that.

Several other Apple products have early Black Friday sales. A few that caught my eye:

- M4 MacBook Air 13-inch (16GB memory/256GB SSD) is $749 (25% off) and a great price on my top recommendation for a computer. I consider 256GB storage to be miserly to the point of malice, so grab an external SSD (a minor hassle, for sure). Or, get the 512GB model for $949 (21% off), a still-quite-good deal.

- AirPods 4 with Active Noise Cancellation are

$110 (39% off)$99 (44% off) and$79$69 without ANC (38%47% off). Go for the ANC. - I wasn’t aware Beats made cables, but their USB-C to USB-C Woven Cable (5 ft/1.5 m) in Surge Stone is $8.50 (55% off).

- I paid full price for my iPhone 17 Pro Silicone Case in Midnight a month ago; it’s now

$36 (27% off)$25 (49% off) along with most other colors, except Terra Cotta, which is $34 (30% off).

(Amazon affiliate links, natch. Make me filthy rich.)

More on Saudi Arabia’s ‘Gameswashing’ ⚙︎

From the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast, episode 302—“Saudi Arabia is Using Games to Improve Its Image” (Overcast, Apple Podcasts):

Paris Marx is joined by Nathan Grayson to discuss how Saudi Arabia is buying its way into the sports, comedy, and video game industries in order to broaden its investment portfolio and launder its international reputation.

Grayson is a cofounder of Aftermath, “a worker-owned news site covering video games, the internet, and the cultures that surround them.”

I found this conversation valuable as an explainer for the “why” behind Saudi Arabia’s ongoing games- and sportswashing that was briefly mentioned in the aforelinked Karen Attiah “Saudification” post.

In addition to laundering its image (and its oil money), the other beneift Saudi Arabia’s may see to its gaming takeover is that control over video games means control over young, impressionable men. Think Madden Football, UFC, Battlefield, or Mass Effect. The ability to control (or at least influence) the content and imagery in these games can have a huge long-term effect—I imagine, for example, we’d see less of the “Middle East as the enemy” trope in first-person shooter games, and perhaps more examples of the “advantages” of an absolute, totalitarian, patriarchal monarchy.

Karen Attiah: ‘The Saudification of America Is Under Way’ ⚙︎

Karen Attiah, The Guardian:

This week, seven years almost to the day since the CIA announced the crown prince’s responsibility in the murder [of Jamal Khashoggi], Mohammed bin Salman returns to Washington, invited for an offical visit by America’s Temu pharaoh, Donald Trump. The reconciliation between Trump and MBS was perhaps inevitable, given that even before the first Trump presidency, Trump spoke often of his love for the Saudis and their wealth. (“I get along great with all of them; they buy apartments from me. They spend $40m, $50m,” he quipped in 2015. “Am I supposed to dislike them? I like them very much!”)

Attiah, who was until recently the editor of the Washington Post’s global opinion section, hired Khashoggi in 2017.

A year later, Saudi Arabia had Jamal killed. In the aftermath of Jamal’s murder, Trump administration officials worked overtime to launder Saudi Arabia’s blood-stained image. Jared Kushner was advising Prince Mohammed on how to “weather the storm”. Last year, Kushner’s equity firm received $2bn from Saudi Arabia’s private equity firm.

There’s much to say about the Saudification of western cultural spaces through the sheer sums of money the kingdom is so obviously throwing into what it sees as soft power. Writers and observers have commented for years about Saudi Arabia’s “sportswashing”, like the kingdom’s sponsorship of LIV golf tournament and the purchase of the Newcastle United soccer team.

“Gameswashing” too: Pokemon Go (and its location data) for $3.85 billion, Electronic Arts ($55 billion), and many more.

Attiah again, this time on her personal site, The Golden Hour:

Yesterday, ABC news reporter Nancy Bruce asked the question of MBS. “Your royal highness, the U.S. concluded that you orchestrated the brutal murder of a journalist. 9/11 families are furious that you are in the Oval Office. Why should Americans trust you?”

At first, the crown prince smirked at the camera during the mention of 9/11 families. Then, seconds after that question about Khashoggi’s murder, the millennial crown prince looked down, fidgeting with his hands like a nervous schoolchild called into the principal’s office. And he let Trump do the dirty work -to attack ABC as fake news before launching into more vile commentary and smearing Jamal’s name:

“You’re mentioning someone [Khashoggi] who was extremely controversial; a lot of people didn’t like that gentleman that you’re talking about. Whether you like him or didn’t like him, things happen,” Trump said.

The written word doesn’t do the quote justice. The malice oozing from Trump as he spews out “a lot of people didn’t like that gentleman” needs to be seen and heard to fully comprehend its odiousness.

That’s in addition to Trump’s vile and appalling implication that murder—dismemberment—is, perhaps, somehow, acceptable if you’re “controversial” or disliked, a perfectly reasonable consequence in Trump’s twisted, mob-boss mind.

Trump’s Grip on His Nastiness Is Slipping ⚙︎

Margaret Sullivan, The Guardian:

Catherine Lucey, who covers the White House for Bloomberg News, was doing what reporters are supposed to do: asking germane questions.

Her query to Donald Trump a few days ago during a “gaggle” aboard Air Force One was reasonable as it had to do with the release of the Epstein files, certainly a subject of great public interest. Why had Trump been stonewalling, she asked, “if there’s nothing incriminating in the files”.

His response, though, was anything but reasonable.

It was demeaning, insulting and misogynistic.

He pointed straight at Lucey and told her to stop doing her job.

“Quiet. Quiet, piggy,” said the president of the United States.

Donald Trump has never been a nice man, but he’s generally managed to maintain an in-public grip on his vituperativeness, especially in front of the cameras.

That grip is slipping.

Like Sullivan and others, I’m shocked-not-shocked by Trump’s explosion of anger toward a female reporter, but I’m genuinely dismayed that the other reporters around him didn’t bat an eye. The male reporter to his left displays no reaction whatsoever and the female reporter whose question Lucey was supposedly interrupting just… asks it. No hesitation, no surprise. Seemingly just another outburst the press has come to expect—and ignore.

What I find deeply disturbing—and why I say he’s losing some of his self-control—is the suddenness of his outburst and the equal speed with which he regains his composure. Note how calmly he answers a question before his eruption, and how calmly he answers after.

His first “quiet” to Lucey is angry, as he raises his finger in admonishment. It’s the level of anger from someone who’s pissed off at being interrupted.

His second “quiet” is menacing, an escalation as he lunges toward Lucey and thrusts his finger right in her face, an attempt to intimidate, dominate. This is the moment he lost self-control. You can imagine Trump shoving her, or slapping her, to shut her up.

Calling her “piggy”—an epithet seemingly expressing his deep personal disdain for the reporter—feels almost tacked on. He knows he can’t physically strike Lucey, but he needs to strike out at her. He needs to insult her, put her down. This is the moment Trump’s survival instincts kick in, but he’s not yet fully back in control. He can’t help himself, and out slips “piggy,” one of his favorite misogynistic yet comparatively “polite” insults.

But I’ll bet you that wasn’t the word he was thinking.

Cynthia Erivo and Misty Copeland Perform Stripped-Down Version of ‘No Good Deed’ ⚙︎

The YouTube algorithm at its best. Beautiful.

Cynthia Erivo on Fresh Air ⚙︎

I throughly enjoyed this conversation between Cynthia Erivo and Tonya Mosley on Fresh Air (Overcast, Apple Podcasts). Mosley asks great questions, and Erivo has wonderful, thoughtful answers. It’s in support of Erivo’s newly-released memoir, Simply More: A Book for Anyone who Has Been Told They're Too Much (Amazon, Bookshop, Apple Books) and of Wicked For Good, which comes out Friday (I’m excited for part two, despite some concerns induced by the stage production, which I thought dragged in the second act).

I also recently watched the season two opener of Poker Face, in which Erivo deftly plays quintuplets. She is ridiculously talented.

Apple 3D-printed Titanium Apple Watch Cases, Cutting Material Use by 50 Percent ⚙︎

Apple details a new manufacturing process for its titanium Apple Watch cases:

It started with a pie-in-the-sky idea: What if 3D printing — historically used to create prototypes — could be leveraged to produce millions of identical enclosures to Apple’s exact design standards, with high-quality recycled metal? […]

This year, all Apple Watch Ultra 3 and titanium Apple Watch Series 11 cases are 3D-printed with 100 percent recycled aerospace-grade titanium powder, an achievement not previously considered possible at scale.

I found this story utterly fascinating. It’s an example of Apple creating truly innovative processes to solve tough materials science challenges (like needing to atomize the titanium into powder by “fine-tuning its oxygen content to decrease the qualities of titanium that become explosive when exposed to heat”). As a software guy, I find this manufacturing stuff deeply riveting.

I own an Apple Watch Ultra 3 (in black), and I had no reason to notice a change: the quality seems as high as ever.

One curiosity:

Using the additive process of 3D printing, layer after layer gets printed until an object is as close to the final shape needed as possible. Historically, machining forged parts is subtractive, requiring large portions of material to be shaved off. This shift enables Ultra 3 and titanium cases of Series 11 to use just half the raw material compared to their previous generations.

“A 50 percent drop is a massive achievement — you’re getting two watches out of the same amount of material used for one,” Chandler explains. “When you start mapping that back, the savings to the planet are tremendous.”

In total, Apple estimates more than 400 metric tons of raw titanium will be saved this year alone thanks to this new process.

(That’s Sarah Chandler, Apple’s vice president of Environment and Supply Chain Innovation.)

Creating two watches from the same amount of raw titanium previously used for one watch is indeed great for the planet, but I can’t help noticing that Apple hasn’t lowered the price of the Apple Watch to account for the reduced material cost, suggesting the reduction is also good for Apple’s bottom line.

Update: My friend and former colleague Matt did some back-of-the-envelope math (sparking me to do the same) which suggests Apple’s per-watch savings might (generously) amount to no more than 50¢–$1 per case—scarcely enough to move the retail price, even with Apple’s high margins. The effect on its bottom line would likewise be minuscule: assuming 5 million titanium watches sold, Apple could save $2.5–$5 million annually—a rounding error for the company. I hereby rescind my snark and acknowledge that Apple may in fact be doing this purely to benefit the planet.

Jeff Williams Is Officially Retired From Apple ⚙︎

Marcus Mendes, 9to5Mac:

Last July, Apple announced that its longtime Chief Operating Officer, Jeff Williams, would retire “late in the year.” According to Bloomberg’s Mark Gurman, he just clocked out for the last time.

His name and photo have been removed from Apple’s leadership page.

Which reminded me: a couple of weeks after his announced retirement, I ran into Williams on a flight from the Raleigh/Durham airport to San Francisco. He (like me) was returning home from a family visit. I congratulated him on his pending retirement, noting that I’d recently taken the step. He asked for retirement advice. We both laughed.

During the flight, he was reading Life Worth Living: A Guide to What Matters Most (an actual book, not from Apple Books). It’s described as “a guide to defining and then creating a flourishing life, and answering one of life’s most pressing questions: how are we to live?” and is based on a popular course at Yale. He was clearly preparing himself for an after-Apple future.

I wish him well.

(And Jeff, if you read this, reach out… there’s an after-Apple Slack channel invite waiting for you!)

Accessing the OED via Your Local Public Library

Accessing the Oxford English Dictionary normally costs $10/£10 a month (or $100/£100 a year), but many libraries offer free access—handy if you need to, say, refute an annoyingly ahistorical use of “weed”.

To find access instructions for your library, plug “access OED public library <your city>” into your search engine of choice. For example, “access OED public library San Francisco” leads you to this SFPL FAQ. You may need to dig a bit. Or contact your librarian.

I’m suggesting a web search because, although the OED has a “Sign in with library card” option, the list of available libraries is woefully outdated (it doesn’t show SFPL, for example) and accessing the option isn’t obvious. If you’d like to try your luck, here’s how:

- Go to OED.com.

- Select the account sign-in icon at the top (a blue head in a white circle).

- Select “Sign in with library card.”

- Search for your library. (Good luck.)

(Worth noting: several libraries offer non-resident memberships, usually for a nominal annual fee, if your local library doesn’t offer OED access. Also useful for borrowing books via Libby or Hoopla.)