Fast, private email hosting for you or your business. Try Fastmail free for up to 30 days.

‘Inside Trump’s Head-Spinning Greenland U-Turn’ ⚙︎

The Wall Street Journal (gift link; Apple News+ link):

When President Trump arrived in the snow-covered Swiss Alps on Wednesday afternoon, European leaders were panicking that his efforts to acquire Greenland would trigger a trans-Atlantic conflagration. By the time the sun set, Trump had backed down.

The about-face followed days of back-channel conversations between Trump, his advisers and European leaders, including NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, according to people close to the talks. The Europeans, who stood united in their opposition to Trump acquiring Greenland, employed a mix of enticements, such as offers to boost Arctic security, and warnings, including about the dangers to the U.S. of a deeper rupture in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

After a meeting with Rutte on Wednesday, Trump called off promised tariffs on European nations, contending that he had “formed the framework of a future deal” with respect to the largest island in the world.

In other words, Trump caved, because Trump Always Chickens Out. I’m sure a massive market drop helped—Trump’s billionaire cronies couldn’t have liked that.

We can also add “framework of a future deal” to “concepts of a plan” and “two weeks” as phrases which succinctly illustrate Trump’s inability to solve real-world problems and offer actual solutions.

White House Posts Altered Photo of Minnesota Protester Following Her Arrest ⚙︎

Maggie Harrison Dupré, Futurism:

The White House published an image on X in which the face of a protester had been altered using AI to depict her weeping during her arrest – instead of striking a stoic pose, as she actually looked during the event.

The woman in the image, civil rights attorney and organizer Nekima Levy Armstrong, was arrested this week after interrupting a church service in St. Paul, Minnesota.[…]

On Thursday, DHS Secretary Kristi Noem published a photo on X of Levy Armstrong’s arrest. Levy Armstrong appears to be handcuffed as she was escorted through an office space by a federal agent. In this image, Levy Armstrong isn’t crying. She’s also wearing bright pink lipstick, and her mouth is closed.

Roughly 30 minutes later, things got decidedly more bizarre when the official White House X account also published an image on X purportedly depicting Levy Armstrong’s arrest. But in this version of the photo, Levy Armstrong is pictured sobbing, with visible tears streaming down her cheeks and her mouth open. Her pink lipstick, notably, is gone.

The White House post has a community note that the image was digitally altered, proving that even on the hell site, people still recognize bullshit.

White House spokesperson Kaelan Door defended the doctored photo, writing “The memes will continue.” A fake photograph presented as real on an official White House communications channel isn’t a meme. It’s propaganda.

Sinners Shatters Oscar Records with 16 Nomination ⚙︎

Ryan Coogler has officially rewritten Oscar history.

Coogler’s “Sinners” shattered the Academy Awards’ all-time nomination record Thursday, earning 16 nods and surpassing the previous mark of 14, held by three films. […]

The supernatural thriller received nominations for best picture; director; actor (Michael B. Jordan); supporting actress (Wunmi Mosaku); actor in a supporting role (Delroy Lindo); original screenplay; casting; production design; cinematography; costume design; film editing; makeup and hairstyling; sound; visual effects; original score; and original song for “I Lied to You.”

OK, fine, I’ll watch the damn movie.

Baseball’s Selective Hall of Fame

Tyler Kepner, writing in The Athletic :

Carlos Beltrán and Andruw Jones, graceful center fielders and slugging stalwarts of the 2000s, were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on Tuesday in voting by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. The pair will join Jeff Kent, a second baseman elected by an era committee last month, at the July 26 ceremony in Cooperstown, N.Y.

I hate all three selections, and not (just) because of their career numbers.

Beltrán was a solid slugger, with 435 home runs and a .279 batting average, and a consistent base swiper (312 stolen bases). He had a cup of coffee with the San Francisco Giants in 2011, collecting his 300th home run on a Splash Hit into McCovey Cove, after six years with the New York Mets. He was also the putative ringleader of the Astros’ “bang-the-can” sign stealing scandal during their World Series championship season, leading to massive fines and firings, including Beltrán’s eventual dismissal as Mets manager.

Jones was also a strong hitter (434 home runs, .254 batting average), and an outstanding center fielder (10 Gold Gloves). He played primarily for the Atlanta Braves, so as a Mets fan I have a natural distaste for him. He was arrested on accusations of battery against his wife.

Kent was a stellar second baseman throughout his career, but most especially with the Giants. He hit 377 home runs (more than any other second baseman in MLB history), with a career batting average of .290 and 1,518 RBI. (He was also with the Mets during a terrible stretch, even by Mets’ standards, and still managed to put up very strong numbers.) He was a good player throughout his career, but it was with the Giants where he achieved greatness. He’s also a massive jerk who, among other things, supported a ban on same-sex marriage in California.

The Baseball Hall of Fame has a “character clause” that voters are supposed to use when deciding who gets in and who doesn’t:

Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contribution to the team(s) on which the player played.

This clause is discretionary, subjective, and inconsistently applied.

Here we have three soon-to-be Hall of Famers, each with arguably HoF-worthy careers, each with a significant failing of integrity, sportsmanship, or character. These players’ numbers are sufficient to be elected to baseball’s highest honor despite their failings.

And yet Barry Bonds—seven-time MVP and baseball’s home runs and walks leader who, by any objective measure, outshines all three—will never make it to the Hall of Fame because of accusations of performance-enhancing drug use.

For the record: Bonds was a career .298 hitter, with 1,996 RBI, 2,558 walks, and 514 stolen bases. Oh, and 14 All-Star appearances, 12 Silver Sluggers, 8 Gold Gloves, and holds the MLB home run records for a single season (73) and all-time (762). He was a generational player.

Kent’s inclusion is especially galling as a Giants fan, because he benefited immensely from having Bonds in the lineup. Kent—who was booed when his name was announced in December, on the same ballot as Bonds—has a career slash line (.289/.358/.489/.847) that’s well below that of his Giants era (.297/.368/.535/.903). If you remove those prodigious Giants years, his numbers drop even further: .284/.350/.445/.795. Would Kent even be sniffing at the Hall of Fame without Bonds? I doubt it.

I’m not excusing the allegations against Bonds. As I wrote of Pete Rose after he was posthumously removed from the Hall of Fame’s “permanently ineligible list”:

I’ve long held that the Baseball Hall of Fame should be stats-based. If you top the leaderboards, you should be eligible. […] it makes no sense to visit Cooperstown and not see the game’s most prolific hitter on display.

The same is true about Bonds. If you can ignore “integrity, sportsmanship, and character” for these three players, with their numbers and their failings, but not for Bonds, it isn’t about numbers nor failings. It’s punitive. And personal.

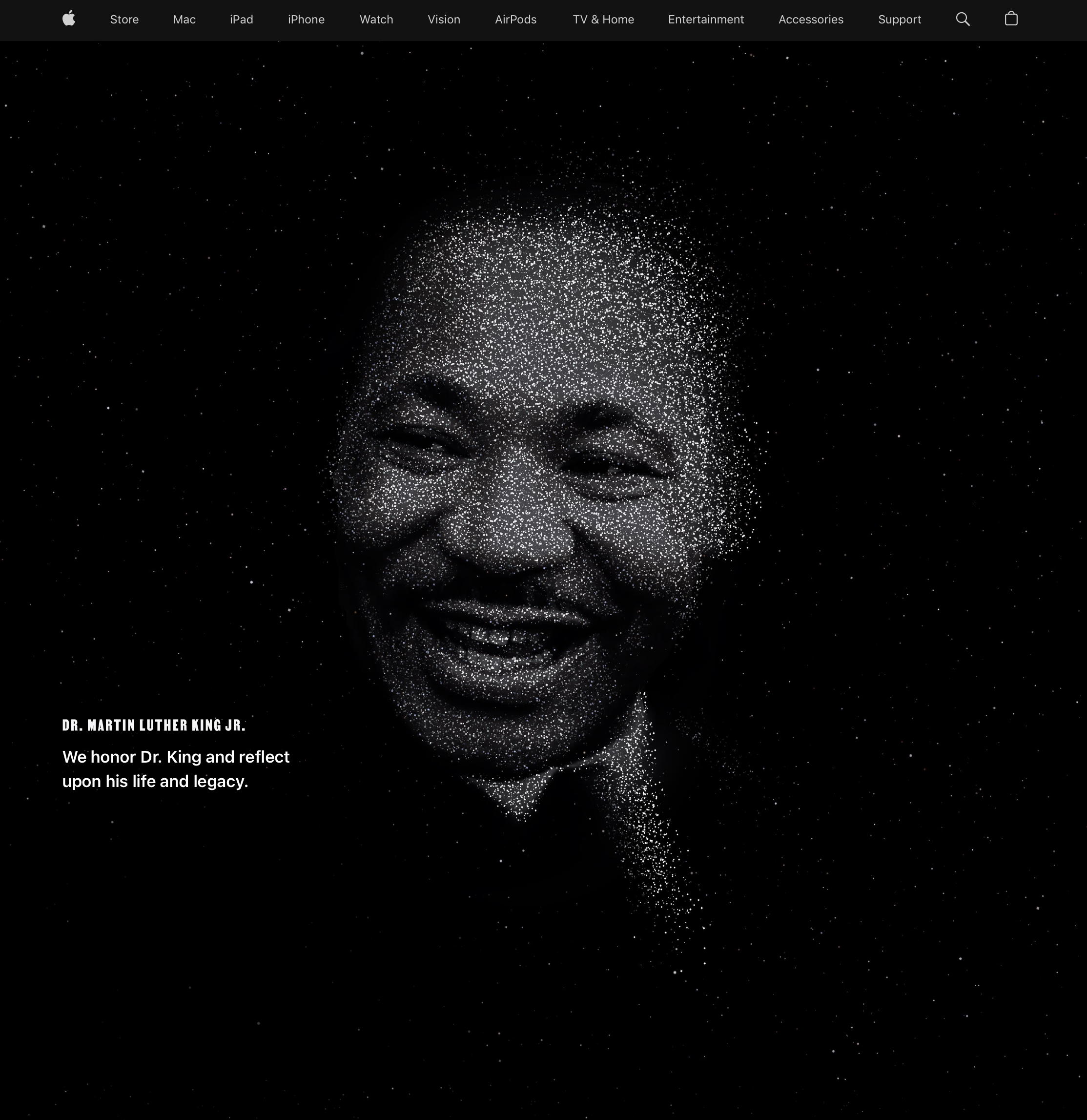

Apple ‘Honors’ Martin Luther King While Working Against His Legacy

Apple replaced its homepage with a tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as it has each MLK Day since at least 2015.

For the first time in that decade, I’m no longer confident Apple still believes in the teachings of Dr. King. Individuals? Yes. The company writ large? I’m doubtful.

Last MLK Day—which coincided with Donald Trump’s second inauguration—I wrote of Apple’s use of specific MLK quotes:

Education against propaganda, the importance of thinking critically, concern for others, the dangers of selfishness, and using your voice… I can’t definitively say Apple intended these quotes to speak to the challenges this country faces at this moment, but I’m confident they were chosen deliberately.

This year, Apple selected these quotes:

- “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’”

- “I am convinced that love is the most durable power in the world.”

- “Be a bush if you can’t be a tree. If you can’t be a highway, just be a trail. If you can’t be a sun, be a star. For it isn’t by size that you win or fail. Be the best of whatever you are.”

Again, I’m confident they were chosen deliberately—but this year I don’t see a message of resistance or solidarity. Instead, they raise uncomfortable questions:

- Is banning ICEBlock—which warned citizens of ICE raids that have now turned deadly—what Apple is doing for others?

- Is appeasing a petty tyrant with shiny trinkets a declaration of love?

- Is allowing apps that generate vile content to remain on the App Store Apple's best?

Dr. King was a radical. Yes, he spoke of peace and nonviolence, and also advocated for dramatic social change and economic justice. Dr. King didn’t encourage passivity, he endorsed disruption. We don’t see Apple sharing these quotes:

- “A time comes when silence is betrayal.”

- “The profit motive, when it is the sole basis of an economic system, encourages a cutthroat competition and selfish ambition that inspires men to be more concerned about making a living than making a life.”

- “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

- “I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values.”

- “The curse of poverty has no justification in our age. It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization.”

- “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

- “One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

- “I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.”

Any of those would be more relevant to this moment, should be welcome on Apple’s website, and would demonstrate moral courage, steadfast conviction, and principled leadership. But they’re too radical for Apple. Instead, Apple launders its reputation through Dr. King while working against Dr. King’s legacy.

Trump’s Message to Norway Is Truly Off-the-Chart Bananas ⚙︎

By now you’ve likely seen the message Donald Trump sent the Prime Minister of Norway, Jonas Gahr Støre—and if you haven’t, congratulations on avoiding this dumpster fire. There’s still time to turn away.

As reported in The New York Times (gift link) and seemingly everywhere else:

Dear Jonas: Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace, although it will always be predominant, but can now think about what is good and proper for the United States of America. Denmark cannot protect that land from Russia or China, and why do they have a ‘right of ownership’ anyway? There are no written documents, it’s only that a boat landed there hundreds of years ago, but we had boats landing there, also. I have done more for NATO than any other person since its founding, and now, NATO should do something for the United States. The World is not secure unless we have Complete and Total Control of Greenland. Thank you! President DJT

Most of the coverage treats the message “seriously,” by which I mean “worthy of consideration” rather than as the nonsensical ravings of a lunatic mind. Instead they parse, fact check, and contextualize it, giving his words greater weight and meaning than exists—or deserves. A few, like Anne Applebaum’s piece in The Atlantic (Apple News+ link), recognize the message as yet another sign of Trump’s cognitive break from reality and continuing inability to perform the role of president.

I can’t get over the immaturity of the writing.

It’s juvenile, muddled, bombastic, and utterly, utterly incoherent. Yes, it’s factually inaccurate (his knowledge is at the summarizing-the-CliffsNotes level), but worse is there’s no logic, no nuance, and absolutely no consideration of the real world.

It’s a dictated first draft, sent with the self-satisfied smugness of someone who spent his entire life pretending to be smart while surrounding himself with people who coddled him and sane-washed his words—and now refuses to let anyone edit his “brilliance.” It’s pure cosplay, an attempt to emulate how serious people communicate, but with insufficient intellectual heft and mastery of language to compose a persuasive, well-reasoned paragraph that goes beyond “I believe therefore I’m right.”

This message exposes many of Trump’s worst flaws: limited knowledge, incurious, self-delusional, transactional, self-centered. It reads like that of a man who never advanced—intellectually, socially, morally—beyond high school.

High schoolers would scoff at Trump’s simplistic, disjointed, egotistical writing—as should we all.

‘Drawing Comics Because the World is Awful’ ⚙︎

Morgan Gold, on why he draws comics (on Substack, sadly):

Comics have a peculiar magic: they can smuggle ideas and challenge injustice in ways that words alone cannot. […]

TikToks and tweets can be useful in political turmoil. Their strength isn’t depth. It’s speed and realism. A tweet can put a feeling into plain words and make it portable. Videos go further by creating a sense of being there. Sometimes it is carefully edited persuasion. Sometimes it’s raw footage to serve as evidence. Sometimes it is a parasocial lifeline, like a FaceTime with a friend. These media can witness, rally, soothe, or inflame. And much like a gas station burrito, they pass through you quickly. And then it’s on to more. Keep reacting. Keep scrolling.

Comics are different. They wait for you. They tell the story at the reader’s pace. Each panel is a bite-sized chunk of the story. Words and pictures conveying ideas and/or stories. Comics do a wonderful job of taking an abstraction—a policy, an injustice, a sinking feeling of dread—and give it a face. You can make it discussable. You can make it mockable. Going from panel to gutter and then panel again, you can look at the monster from a safe distance and acknowledge the reality of it without being ruled by the feeling.

Gold opens his essay with a comic (naturally) of ICE recruits learning how to terrorize, the first panel of which is “Today’s Lesson: How to turn a school drop-off into a war zone.” Rule number one: “Always create your own danger.”

Latent America: The Nation That Would Exist If… ⚙︎

Adam Bonica, last week:

Americans work longer hours, pay more out-of-pocket for college and childcare, lack parental leave, and enjoy less economic mobility. The share of income going to the top 1 percent is nearly double the OECD [the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] average. American CEOs earn, on average, 354 times as much as their workers. More workers are trapped in poverty-wage jobs. Collective bargaining covers fewer workers. And social protections are less generous for those who fall on hard times, with the government raising less in taxes and spending more on the military.

The economy is just the beginning.

We spend nearly twice as much on healthcare as other wealthy countries do. Yet life expectancy is well below average, infant and maternal mortality rates are alarmingly high, and more Americans remain uninsured.

This article came up over lunch with some friends as we lamented the greed of America’s billionaires, who would rather leave California than pay an additional 5% of their assets—an amount they’d hardly miss, from assets which in the last year have often risen by more than the tax they’d owe.

If billionaires were willing to settle for ever-so-slightly-less excessive wealth, the lives of non-billionaire Americans could be improved immensely.

Universal healthcare is not some utopian fantasy. It is Tuesday in Toronto. Affordable higher education is not an impossible dream. It is Wednesday in Berlin. Sensible gun regulation is not a violation of natural law. It is Thursday in London. Paid parental leave is not radical. It is Friday in Tallinn, and Monday in Tokyo, and every day in between.

There is another America inside this one, visible in the statistics of nations that made different choices. Call it Latent America: the nation that would exist if our democracy functioned to serve the public rather than protect the already powerful.

To see this, you need only compare outcomes in the US with its peers. The graphic below illustrates a simple thought experiment: What would happen if the United States simply matched the average performance of our 31 peer nations in the OECD? We don’t need to become a shining city on a hill to transform Americans’ lives. We just need to become average.

Bonica includes a set of charts that illustrate what becoming “average” looks like. For example:

- $19,000 more income, and $96,000 more wealth per household

- 26 million more people with health insurance, and $2.1 trillion less in annual healthcare spending

- 25 weeks of guaranteed paid new parental leave (up from zero leave)

- 5 million fewer children in poverty

- 10,000 fewer infant deaths, and a 76% drop in maternal deaths during childbirth

- 35,000 fewer gun deaths a year, and 99% fewer school shootings

There are so many more potential societal improvements, just from America achieving the average of its thirty-one wealthy democratic peers.

Bonica’s argument is inherently optimistic, seeing the comparisons to our peers and the moment we’re in—the shameless corruption, the dismantling of institutions, the dehumanization—not as pointing to an ending, but as “a set of solutions waiting to be implemented.”

Via Jason Kottke, who observes:

Imagine if the US took its exceptionalism seriously and tried to maximally improve the lives of its citizens & residents instead of generating, as Bonica puts it, “enormous prosperity while deliberately withholding it from those who need it most”.

I may not fully share Bonica’s optimism, but the alternative is to believe that America is simply incapable of achieving what so many of its peers already have. If Americans truly believe in American Exceptionalism, then we must all demand more of our politicians, our billionaires, and ourselves.

The New York Times Analyzes ICE Agent Jonathan Ross’ Cellphone Video ⚙︎

The New York Times performed a second video analysis (gift link) of the killing of Renee Nicole Good, this time with video from the cellphone of Jonathan Ross, the ICE agent who shot Good three (or four) times. The Department of Homeland Security released that video in an effort to exculpate Ross and prove he was “run over,” while White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt called for the New York Times to “update their reporting on the ICE Agent’s self defense.”

The Times complied, syncing this new video with the others they previously analyzed.

It didn’t help the agent at all.

Instead of proving Ross was run over, it showed that he:

- was a couple of feet in front of the car as it turned away from him;

- leaned forward on the car (apparently for balance) and was possibly being pushed backward by the car;

- managed to maintain a grip on his cellphone while he shot at Good.

It also records that his first instinct upon shooting a woman three (or four) times was to call her a “fucking bitch.”

This was their defense.

I’m struck by the monumental arrogance it takes to release this video and claim it vindicates Ross.

The cry from the White House and right-wing nut jobs was that Ross was “run over.” But his own video shows that he was never on top of or under the car. At best, he briefly lost his footing on the icy asphalt, used the car to brace himself, and was pushed a couple of feet as the car turned away from him. He regained his balance quickly enough to fire, one-handed, into a moving vehicle. And then exclaim “fucking bitch.”

Absolutely pathetic. Arrest and charge Jonathan Ross.

Jamelle Bouie: Abolish ICE ⚙︎

Jamelle Bouie last week, following the killing of Renee Nicole Good by ICE agent Jonathan Ross:

Abolish ICE. […]

ICE acts more like a Gestapo than it does any kind of legitimate law enforcement agency. […]

This year is obviously the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and for my vantage point, this looks like a Boston Massacre. This looks like the kind of event that can and should galvanize people against this administration, which wants to subject the entire American people to tyranny, to exploitation, to domination. This is an illegitimate president. ICE on our streets is an illegitimate presence. And let this be at the beginning of the end for ICE and for this White House.

Restrained, direct, unambiguous.

Abolish ICE.

‘What Happens the Moment We Touch Greenland’ ⚙︎

Brent Molnar, in his Voice of Reason newsletter (Substack, alas):

If the United States follows through on the threat to invade Greenland, we need to be crystal clear about what happens the next morning. This is not a real estate transaction or a routine military exercise. It is the geopolitical equivalent of pulling the pin on a grenade in a crowded elevator. The moment American boots hit the ground in Nuuk to seize territory from a fellow NATO member, the world as we know it ends. The consequences will not be temporary sanctions or angry letters. They will be total, permanent, and devastating.

The fall of NATO, “the closure of every U.S. military base on the continent,” Europe dumping their dollar reserves (“sending the value of our currency into a death spiral”), U.S. companies expelled from European markets (“Trillions of dollars in market capitalization will be incinerated in minutes”), U.S. airlines banned from European airspace, the end of visa-free travel to (and legal protections in) Europe.

This is the end of trust, and it does not reset. You cannot invade a democratic ally and then say “my bad” four years later.

The biggest benefit of international cooperation isn’t the loud wars they prevent but the quiet stability they provide.

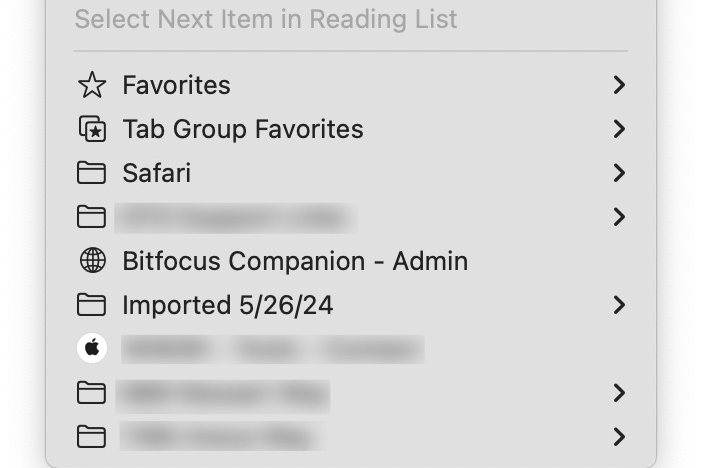

A Brief Addendum to the Apple Creator Studio Announcement on the UI of Apple Pro Apps ⚙︎

While skimming the media photos from Apple Creator Studio announcement, I was struck by the clean minimalism of Apple’s macOS “Pro” apps. They feel like the purest expression of macOS design: appropriately sized interface elements, a reasonable window corner radius, and blessedly little translucency. Controls and content fill the windows with nary a wasted pixel or blurry background in sight. The apps are focused on functionality and stripped of pretentiousness. They bring a sense of calm, orderliness, and clarity of purpose—we’re here to work. I don’t know if the Pro apps’ UI is a refinement of Liquid Glass or a renunciation of it, but it looks like what macOS should be. Even the iPad versions—including the newly released Pixelmator Pro, to a lesser extent—have a more restrained feel. If all macOS apps looked like they do in these perfectly curated marketing materials, I think many people, myself included, would be overjoyed.

Apple Announces Apple Creator Studio, a New Subscription Bundle, and Brings Pixelmator Pro to iPad ⚙︎

Apple today unveiled Apple Creator Studio, a groundbreaking collection of powerful creative apps designed to put studio-grade power into the hands of everyone […]. Exciting new intelligent features and premium content build on familiar experiences of Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, Pixelmator Pro, Keynote, Pages, Numbers, and later Freeform to make Apple Creator Studio an exciting subscription suite […].

Apple Creator Studio will be available on the App Store beginning Wednesday, January 28, for $12.99 per month or $129 per year, with a one-month free trial, and includes access to Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, and Pixelmator Pro on Mac and iPad; Motion, Compressor, and MainStage on Mac; and intelligent features and premium content for Keynote, Pages, Numbers, and later Freeform for iPhone, iPad, and Mac. College students and educators can subscribe for $2.99 per month or $29.99 per year. Alternatively, users can also choose to purchase the Mac versions of Final Cut Pro, Pixelmator Pro, Logic Pro, Motion, Compressor, and MainStage individually as a one-time purchase on the Mac App Store.

Apple could have easily justified $13 a month for Final Cut Pro or Pixelmator Pro alone. If you’re a content creator (or are hoping to become one), gaining access to six “Pro” apps for one price is a screaming good deal.

(Buying the suite of apps individually costs $650—five years of subscriptions—and doesn’t come with Pixelmator Pro for iPad, which is only available with a Creator Studio subscription.)

The “intelligent features and premium content” may be a useful value-add, but I doubt anyone who doesn’t need the Pro apps would subscribe just to gain access. I expect we’ll eventually see another subscription option soon that’s just the Apple Intelligence and premium content, so anyone buying individual apps or using the free iWork apps won’t feel left out. Why leave subscription revenue on the table, right? Apple has to pay for its reportedly $1 billion a year Google Gemini partnership somehow.

Creator Studio includes several AI features that are not available in the apps without a subscription (Warp tool in Pixelmator Pro, clean up slides in Keynote, Magic Fill in Numbers, for example). I’m betting several future Apple Intelligence features will be likewise locked behind a subscription (perhaps part of Apple One or iCloud+).

I have a gnawing unease about locking these features and content behind a subscription. If this bundle proves successful—and I have no reason to believe it won’t—the incentive to put new functionality behind a paywall may prove so tempting that Apple starts littering its apps (and, heaven forfend, operating systems) with “Premium”-tagged menu items, or we’ll see “Subscribe” windows thrown up every time a gated feature is selected. Empty Trash? Subscribe to macOS Tahoe Premium.

I hope I didn’t just type that into existence.

In addition to subscription creep—shifting functionality behind a paygate—I’m also deeply concerned about subscription permanence. On the Creator Studio product page is this FAQ:

What happens to projects and content I created if my subscription ends?

All the projects and content you create with an active subscription to Apple Creator Studio — including any images you generate or add from the Content Hub — remain licensed in the context of your original creation.

Projects in Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, and Pixelmator Pro remain on all your devices, and you can copy or share them to any other device. To open or edit a project, you need to be an active subscriber. Keynote, Pages, Numbers, and Freeform documents remain unchanged and can be edited; however, no new edits using paid features will be possible.

Emphasis most emphatically added.

Translation: Keep paying, or lose access to your work.

I can handle paying a subscription to access compelling functionality. What I can’t accept is a perpetual subscription just to maintain access to my own creations. This issue isn’t unique to Apple—hello, Microsoft 365—but Apple has never paygated my content before.

This feels momentous: for the first time, Apple now has a “pay us or else” model. For many people, that’s a deal breaker.

Wall Street will be thrilled.

Scott Adams, Disgraced Dilbert Creator, Dies at 68 ⚙︎

People Magazine:

Scott Adams has died at the age of 68. Adams first published Dilbert, a comic strip that satirized life in white-collar offices, in 1989. The comic strip became ubiquitous in the 1990s. Dilbert was pulled from wide circulation, however, after Adams degraded Black people in a 2023 rant.

Adams was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2025.

I was an early Dilbert reader. The strip was a mainstay at work. One of the first two books I bought on Amazon.com (in 1998) was The Dilbert Principle (a gift for my mom). I read God’s Debris at the suggestion of a friend and found it compelling if confusing. At some point I bought a Dilbert mug.

Yes, I was a fan.

This, despite having long recognized Adams as a bigot. He claimed he was denied promotions because he was white, while “less-qualified” Black people were promoted above him, despite admitting he was woefully unqualified for the job—and white people were getting promoted, just not him.

But sometime in 2015, 2016, Adams went completely ’round the bend, with his “Donald Trump is a master persuader” BS, his full-throated endorsement of Trump, and a marked shift toward verbalizing his “anti-woke” ideology on his podcast and Twitter. Oh, and Dilbert stopped being funny. It got worse after Trump won the election, and came to a head in 2023 when he declared—during Black History Month!—that Black people were a “hate group.” I found myself semi-regularly antagonizing him (and his defenders) on Twitter—right up until he blocked me.

I haven’t been a fan in a long time.

Living with cancer is awful, and prostate cancer is one of its most devastating forms. So yes—fuck cancer. I take no great pleasure in Adams’ death from this terrible disease.

But I won’t be grieving for him.

See Also: The New York Times’s obituary.

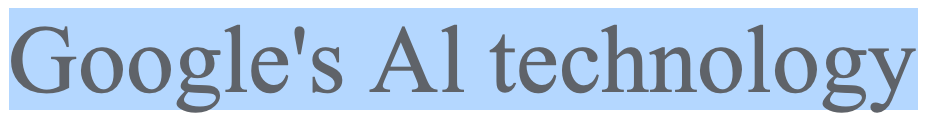

A Pedant’s Aside on the Apple-Google Joint Statement ⚙︎

When writing up the aforelinked joint statement, I kept getting proofreading errors that the “AI” in “Google’s Al technology” was incorrectly spelled.

Here it is, as seen on Google’s site:

You might already spot the problem.

Let’s change the font from that site’s Google Sans to something more distinctive, Apple Chancery:

Are you seeing it? Let me go one step further and use Copperplate, which uses small caps:

Yep, Apple is using “Google’s AL technology” instead of “Google’s AI technology.” I presume there’s a discount for buying a knockoff.

And don’t get me started on Google’s use of straight (“dumb”) quote marks.

Apple Selects Google Gemini to Power Apple Intelligence and ‘a More Personalized Siri’ ⚙︎

Apple and Google, in a rare joint statement to CNBC and subsequently released by Google on its company news site and X/Twitter account:

Apple and Google have entered into a multi-year collaboration under which the next generation of Apple Foundation Models will be based on Google’s Gemini models and cloud technology. These models will help power future Apple Intelligence features, including a more personalized Siri coming this year.

After careful evaluation, Apple determined that Google’s Al technology provides the most capable foundation for Apple Foundation Models and is excited about the innovative new experiences it will unlock for Apple users. Apple Intelligence will continue to run on Apple devices and Private Cloud Compute, while maintaining Apple’s industry-leading privacy standards.

I have many questions, none of which are answered by this brief statement:

- How much money changes hands (and in which direction)?

- Does “based on” mean Apple will augment Google Gemini technology for its needs? Is it then a unique model?

- Will Gemini replace current Apple models in existing features? Will Image Playground, for example, see improvements in quality and style?

- Will OpenAI’s ChatGPT be replaced by Gemini as the “I can’t answer that” escalation, or will Siri simply use Gemini to answer questions directly?

I’m sure further details from Apple will be forthcoming, but for now, Google is carrying the load here: there’s nothing from Apple directly.

It’s worth noting that, as brief as the statement was, it explicitly calls out that Apple Intelligence will “continue to” run locally and on Apple’s Private Cloud Compute—not on Google’s servers. That alleviates a lot of privacy concerns.

This is undoubtedly a sound decision for Apple, both technically and financially, but it must be at least a little disappointing to some on the inside that they’re abandoning—at least publicly—years of internal AI efforts.

It’s a stark and public admission that those efforts were woefully insufficient, and quite the shift from Apple’s usual “Not Invented Here” syndrome.

Silent Sunday

Posted on Mastodon under #SilentSunday, #Photography.

Senators Ask Cook and Pichai to Remove X and Grok From Their Respective Stores ⚙︎

U.S. Senators Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), Edward Markey (D-Mass.), and Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.), in a letter to Tim Cook and Sundar Pichai:

We write to ask that you enforce your app stores’ terms of service against X Corp’s (hereafter, “X”) X and Grok apps for their mass generation of nonconsensual sexualized images of women and children. X’s generation of these harmful and likely illegal depictions of women and children has shown complete disregard for your stores’ distribution terms. Apple and Google must remove these apps from the app stores until X’s policy violations are addressed.

It’s gratifying to see three Senators (all Democrats, it’s worth noting) pressing for action. That it’s only three Senators is pitiful.

Turning a blind eye to X’s egregious behavior would make a mockery of your moderation practices. Indeed, not taking action would undermine your claims in public and in court that your app stores offer a safer user experience than letting users download apps directly to their phones. This principle has been core to your advocacy against legislative reforms to increase app store competition and your defenses to claims that your app stores abuse their market power through their payment systems.

Both Apple and Google have also recently demonstrated the ability to move quickly to moderate apps from the app stores. For example, under explicit pressure, and perhaps threats, from the Department of Homeland Security, your companies quickly removed apps that allowed users to lawfully report immigration enforcement activities, like ICEBlock and Red Dot. Unlike Grok’s sickening content generation, these apps were not creating or hosting harmful or illegal content, and yet, based entirely on the Administration’s claims that they posed a risk to immigration enforcers, you removed them from your stores.

The continued availability of X and Grok from the App Store and Google Play leads me to believe Cook and Pichai are more afraid of incurring the wrath of Elon Musk—and, by extension, Donald Trump—than they are of knowingly, if unwillingly, distributing apps that create, host, and display “nonconsensual sexualized images of women and children.”

Keeping X and Grok after removing ICEBlock undermines Apple’s and Google’s assertions that they apply their guidelines without fear or favor, and weakens their argument that the app review process makes customers safer. If customers can download apps containing harmful and illegal content but can’t download apps that keep them safe, what’s the point of a singular app store or a “rigorous” review process? Either Apple and Google pull X and Grok from their stores or they admit the guidelines are merely convenient fabrications for exerting control.

Why Resizing Tahoe Windows is Hard ⚙︎

Norbert Heger identifies why resizing windows in macOS 26 Tahoe is so frustratingly difficult: thanks to the comically large window corner radius, the area to grab is mostly off the edge of the window:

Living on this planet for quite a few decades, I have learned that it rarely works to grab things if you don’t actually touch them.

macOS Tahoe flips this expectation on its head.

The accompanying gif of him grabbing a plate captures the experience perfectly.

Report Elon Musk’s Apps to Apple ⚙︎

Heidi Li Feldman suggests one small “something” we can all do while we hope regulators ban Elon Musk’s CSAM-sharing X/Twitter:

If you have a moment, file a complaint against X with the Apple App Store.

This is a terrific idea. It signals support from Apple’s customers to take action against Musk’s creepy AI tools and offers a fig leaf to justify pulling the apps from the App Store.

Here’s how to file a report (it took me less than two minutes to file reports against both X and Grok. You can only report apps you’ve downloaded, but both are free and you don’t need to launch them):

- Visit the Report a Problem page for X (Twitter).

- Select Report offensive, illegal, or abusive content.

- Select an appropriate option under Tell us more….

- Provide the necessary details. Restraint is better than bombast. (Feldman’s example—“X is using its AI bot to generate child pornography on demand.”—is appropriately succinct and direct.)

- Repeat for Grok.

Creating and displaying sexualized images of children and non-consenting adults in X and Grok is a clear violation of Apple’s guidelines, in particular:

Apps should not include content that is offensive, insensitive, upsetting, intended to disgust, in exceptionally poor taste, or just plain creepy.

And:

To prevent abuse, apps with user-generated content or social networking services must include:

- A method for filtering objectionable material from being posted to the app […]

(It’s also a more valid application of 1.1 than using it to justify pulling ICEBlock.)

While I harbor few illusions that reporting the apps will lead to Apple actually yanking X or Grok, if enough people lodge complaints, perhaps Apple can muster a meaningful enough threat of removal to spook Musk into addressing the issue. There is precedent: in 2018, Apple pulled Tumblr and Telegram for hosting or sharing child pornography within their apps.

I’m not prepared to accept bets on this happening, though. Apple is quite reticent to threaten big apps with eviction, plus Musk is already suing them on frivolous antitrust grounds. Apple may see pulling his apps as needlessly handing him ammunition—though it may well blow up in his face if he’s obligated to argue that Apple must host apps that create and display child pornography.

‘Elon Musk’s X must be banned’ ⚙︎

Paris Marx on the aforelinked Grok shitshow:

Let’s be honest with ourselves: if a broadcaster or newspaper had started publishing thousands of non-consensual, sexually explicit images of women or — even worse — of children, politicians and regulators would be out for blood. It would be a front-page, ongoing scandal and the organization responsible would be quickly brought to heel because it would be so outrageous.

But when Elon Musk and his chatbot Grok do it, there’s somehow little more than crickets. Politicians are alarmed and say something needs to be done, but can’t quite say what that something is. Regulators say they’re investigating, as thousands more women and children are victimized while the richest man in the world continues treating the whole situation like a big game — or simulation.

Governments must ban X, argues Marx:

Regulators and politicians in some countries have been responding to what’s happening on X. The European Union, United Kingdom, France, and Australia are all investigating the matter, with some even saying what X is enabling is illegal. Indian officials gave X a 72-hour deadline to act on the illegal material, while some Brazilian politicians are calling for the platform to be banned once again. But let’s be real: the responses of regulators to a child porn-producing chatbot on the social media platform owned by the richest man in the world are not nearly strong or quick enough.

Creating a chatbot that victimizes thousands of women on command and generates child pornography should be a red line — and not one you can come back from. Elon Musk and anyone at X or xAI directly working on that functionality should be criminally held to account for the consequences of their actions. But many countries will not have jurisdiction for those crimes. Instead, they should take the obvious move of banning X before the harm it causes their citizens escalates even further.

One place Musk won’t have to worry about a ban is the United States—not while his pedophilia-adjacent buddy is in charge.

‘Grok’s AI CSAM Shitshow’ ⚙︎

Jason Koebler, writing for 404 Media earlier this week (free account required):

Over the last week, users of X realized that they could use Grok to “put a bikini on her,” “take her clothes off,” and otherwise sexualize images that people uploaded to the site. This went roughly how you would expect: Users have been derobing celebrities, politicians, and random people—mostly women—for the last week. This has included underage girls, on a platform that has notoriously gutted its content moderation team and gotten rid of nearly all rules.

The only actions Musk has taken to put an end to this are to issue a weak stop, don’t “threat” and to limit Grok’s image generation and editing to paid subscribers—in other words, monetize the vile behavior. (His investors don’t seem to care, either, investing $20 billion—a ghastly sum of money—into xAI mere days after news of this abuse broke.)

Samantha Cole wrote an extensive follow-up piece for 404 Media (“Grok’s AI Sexual Abuse Didn’t Come Out of Nowhere”):

This is the culmination of years and years of rampant abuse on the platform. Reporting from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, the organization platforms report to when they find instances of child sexual abuse material which then reports to the relevant authorities, shows that Twitter, and eventually X, has been one of the leading hosts of CSAM every year for the last seven years. In 2019, the platform reported 45,726 instances of abuse to NCMEC’s Cyber Tipline. In 2020, it was 65,062. In 2024, it was 686,176. These numbers should be considered with the caveat that platforms voluntarily report to NCMEC, and more reports can also mean stronger moderation systems that catch more CSAM when it appears. But the scale of the problem is still apparent. Jack Dorsey’s Twitter was a moderation clown show much of the time. But moderation on Elon Musk’s X, especially against abusive imagery, is a total failure.

Musk’s failure of moderation is what makes his threat (“Anyone using Grok to make illegal content will suffer the same consequences as if they upload illegal content”) not just meaningless, but disingenuous.

An Observation While Watching the Murder of Renee Nicole Good ⚙︎

One brief observation from watching the New York Times frame-by-frame analysis of the murder of Renee Nicole Good by ICE agent Jonathan Ross (as identified by the Star Tribune):

Ross already had his hand on his gun as Good’s car backed up to leave. Ross shoots Good three times: once through the windshield at an angle, then he reaches through the open driver-side window and fires twice more at Good from point-blank range.

The Star Tribune reports:

“he acted according to his training,” Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, told the Minnesota Star Tribune in an email, noting that this specific agent was selected for ICE’s Special Response Team, is an expert marksman and “has been serving his country his entire life.”

Identifying the man who shot a woman in the head at point-blank range as “an expert marksman” is especially callous and sadistic.

On June 17, Ross was participating in an arrest of Roberto Carlos Munoz-Guatemala, a Mexican citizen, in Bloomington last year. Munoz-Guatemala had previously been convicted of fourth-degree criminal sexual conduct and had been put on a detainer by immigration officials. Munoz-Guatemala ignored the agents’ commands, including to fully roll down his car window, so Ross broke open his rear window and reached inside to unlock the door.

Ross was dragged by the car and required “20 stitches for a deep cut in his right arm and another 13 stitches in his left hand.” JD Vance suggests that justifies the killing:

“That very ICE officer nearly had his life ended … six months ago,” Vance said, referring to the earlier car-dragging incident.

“You think maybe he’s a little bit sensitive about somebody ramming him?”

If he’s still “sensitive” about being “rammed,” he (1) shouldn’t be standing in front of vehicles, and (2) is unfit for duty and shouldn’t have been in the field.

After killing Good, Ross re-holsters his gun as he watches the vehicle spin out of control and crash, then slowly walks toward it. Ross appears calm the entire time—including as he casually asks his colleagues to “call 9–1–1”.

These are not the actions of a man who panicked or feared for his life. They’re the actions of a man who made a deliberate choice to fire his weapon—three times—into a moving vehicle.

Arrest and charge Ross now.

John Gruber: ‘Let’s Call a Murder a Murder’ ⚙︎

John Gruber, linking to the New York Times’ frame-by-frame analysis of the killing of Renee Good in Minneapolis by a mask-wearing ICE agent:

This ICE agent murdered Renee Good, in broad daylight, in front of many witnesses and multiple cameras. Trust the evidence of your eyes and ears.

As a general rule I try to refrain from both watching videos that show people being killed (I find them akin to snuff films) and commenting on breaking news of this nature (there are often too many unknown unknowns).

I made an exception and watched the video, and Gruber is right about two things: this is a murder in broad daylight, and the woman who recorded it, Caitlin Callenson, is an unflinching, steel-spined hero.

Goldman Sachs Exits Apple Card Business; Chase to Become New Issuer ⚙︎

Today, Apple and Chase announced that Chase will become the new issuer of Apple Card, with an expected transition in approximately 24 months.

The Wall Street Journal broke the news (Apple News+) just ahead of the official announcement. Goldman Sachs (the exiting issuer) released its own statement; Chase simply copied Apple’s (and somehow made it uglier). I wonder which of them leaked the deal.

Goldman Sachs has been looking to exit the consumer credit card business for more than two years. The Apple Card has been especially challenging because it has “a high exposure to subprime borrowers and what has been a higher-than-industry-average delinquency rate,” reports the Journal. Chase purchased the portfolio for a $1 billion discount; the Journal notes that discounts “are rare and are reserved for the most challenged cases.”

Proving the difficulty of the business are these two nuggets from the Chase and Goldman Sachs press releases:

Goldman Sachs:

The transaction is expected to result in a $0.46 earnings per share increase to Goldman Sachs’ fourth quarter 2025 results. This reflects a release of $2.48 billion of loan loss reserves reflected in provision for credit losses […]

Chase:

[…] the purchase of the portfolio is estimated to bring over $20 billion of card balances to the Chase platform. […] JPMorganChase expects to recognize a $2.2 billion provision for credit losses in 4Q25 related to the forward purchase commitment […]

Chase’s $2.2 billion reserve on a $20 billion portfolio reflects an approximately 11% expected lifetime loss rate. That’s materially higher than the current ~4% loss rates across all bank credit cards—implying a borrower mix for Apple Card that skews somewhat below “prime” when compared to, say, Chase Sapphire—though we’re not exactly in NINJA-loan territory here.

I can understand why Goldman Sachs wanted out: an 11% expected loss rate—$1 out of every $9 in balances not being collected—is exorbitant for a company more comfortable serving wealthy clients. Chase is treating it as an acceptable risk for their broader credit card portfolio—and they’re operationally and institutionally more capable of supporting the “average” consumer.

Apple also released a set of Frequently Asked Questions (at the distinctive “learn.applecard.apple” URL), the answers to most of which are variations of “nothing changes” or “stay tuned.”

I’ve been a Chase credit card customer for well over a decade; my most used card is with them. I’ve never had any issues, so this transition should be a non-event. Not addressed in the announcement or FAQ is whether Apple Card will (eventually) show up alongside other Chase-issued cards on their (surprisingly good) website (and app) or remain locked away behind the functionally stunted Apple Card site and Apple Wallet. For now, I’ll assume that Apple will continue to maintain full operational control while Chase acts only as the issuer, meaning it won’t integrate the card with its site, which would be a shame.

WSJ Claims AbbVie to Buy Revolution Medicines, AbbVie Says ‘Nope’ ⚙︎

It was a roller coaster day at RevMed, where my wife works. The Wall Street Journal (Apple News+), in a report by Jonathan D. Rockoff, Lauren Thomas, and Cara Lombardo at 2:48 pm EST today:

AbbVie is in advanced talks to buy cancer-drug biotech Revolution Medicines, according to people familiar with the matter.

Revolution Medicines has a market value of around $16 billion. It couldn’t be learned how much AbbVie is offering, but including a typical deal premium, Revolution could be valued at around $20 billion or more.

A deal could come together soon, granted the talks don’t hit any last-minute snags, the people said.

The news sent Revolution Medicine’s (RVMD) stock soaring as much as 30%, briefly touching $105, while AbbVie’s (ABBV) stock saw a comparatively modest 5% surge from its open.

Ninety minutes later, Puyaan Singh at Reuters reported there’s no such deal in the works:

AbbVie on Wednesday denied it was in talks to buy Revolution Medicines […]

The company “is not in discussions with Revolution Medicines,” AbbVie said in an emailed statement to Reuters.

Revolution Medicines dropped nearly 14% after hours, and AbbVie lost most of its gains, too.

Three possibilities occur to me:

- The WSJ completely bungled their facts.

- Someone successfully leveraged WSJ for stock manipulation.

- The leak caused one party to walk (“is not in discussions”).

Whatever the reason, someone undoubtedly made oodles of money, and the Wall Street Journal is wiping egg from its face.

Update: The WSJ has now revised their headline, from “AbbVie Near Deal for Revolution Medicines” to “Revolution Medicines Draws Takeover Interest,” with a subhead “AbbVie said to be among suitors.” The paper also congratulated itself on the rise of RevMed (“Its shares were trading up around 30% after the Journal’s report”).

White House Ficdep Launches January 6 Historical Negationism ⚙︎

Donald Trump’s Ministry of Truth Fiction Department rewrites January 6 history:

The Democrats masterfully reversed reality after January 6, branding peaceful patriotic protesters as “insurrectionists” and framing the event as a violent coup attempt orchestrated by Trump—despite no evidence of armed rebellion or intent to overthrow the government.

And:

Following the President’s speech, the massive crowd peacefully marches down Constitution Avenue to the Capitol to protest the certification of the fraudulent election. The march is orderly and spirited, with flags, signs, and chants supporting President Trump.

Someone should demand Trump and his lackeys watch the videos and explain how beating police officers is “peaceful” and smashing windows is “spirited.”

Placing Nancy Pelosi’s “I take responsibility” quote front-and-center is especially galling if you actually watch what she said instead of relying on Trump’s mischaracterization.

George Orwell, 1984:

Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

We’re solidly into doublethink territory.

NPR’s Visual Archive of the January 6 Attack ⚙︎

NPR compiled an expansive, meticulously maintained visual record that reconstructs the January 6 attack and its aftermath:

In the immediate aftermath of the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, American political leaders almost universally condemned the riot as an act of domestic terrorism that threatened democracy. Now, President Trump calls Jan. 6 a “day of love” and the rioters “great patriots.” And since he issued mass pardons to the rioters, his administration has been trying to rewrite history.

NPR has tracked every Jan. 6 prosecution in a public database, and, drawing on thousands of hours of footage and years of reporting, created a front-line account of the riot. The evidence vividly shows the planning for “revolution” and the brutality of violence on a day that continues to shape American politics.

Seeing all of the threads chronicled in an interconnected timeline underscores the level of coordination across disparate groups, even if it wasn’t collectively “planned.” Utterly damning. A historic act of journalism.

‘The January 6th Insurrection Didn’t Fail, it Just Took Five Years’ ⚙︎

John Pavlovitz (on Substack, alas):

Five years ago, I would have bet my house that Republican voters’ patriotism, faith convictions, and simple humanity would have surfaced, and they would reject this violent lawlessness once and for all.

And as that January night turned to morning and as the scale and severity of what we’d witnessed and how close we all came to losing our Democracy became clear, I remember thinking to myself, “There is no way they will double down on this or on him now, or ever again.”

I was spectacularly wrong.

I remember watching, slack-jawed and fearful for our republic, as a violent mob breached the Capitol live on TV, raised the Confederate flag in that building for the first time in our history, and called for the assassination of lawmakers, all while the president of the United States reveled in the chaos and did nothing to end it.

I wrote then:

This is an attack on the American government, instigated and encouraged by a sitting president, in an illegal attempt to keep him in power.

This is no longer a theoretical coup attempt. This is an actual coup attempt. Whether it succeeds or not, it must be reported as such.

I also wrote:

This day will be read about in history books in every country in the world. This will be the legacy of Donald J. Trump.

I was not confident Trump would walk out of the White House voluntarily on January 20. And even if he did, I was deeply concerned that he would still have the attention of millions of people willing to commit armed insurrection in his name.

But once Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were certified, and the “peaceful” transfer of power did occur, and Trump did leave the building (if not exactly “willingly”), I became confident that Trump was done politically and that the inexplicable allure of Trumpism had finally dissipated.

How naïve.

I anticipated “one-term president who instigated an insurrection in a failed attempt to maintain power” as the one-line brief of his presidential biography and opening sentence to his eventual obituary.

Instead it will be “two-time president and convicted felon, who, despite instigating an insurrection, convinced 77 million voters to elect him for a second term, during which he constructed deportation camps; destroyed the East Wing; terrorized Americans with his “ICE” police force; illegally deported immigrants; abducted the president of Venezuela; enriched himself, his family, and his cronies via grift and patronage…”

Pavlovitz, again:

January 6th should have been America’s second chance at life; a moment for us to speak unequivocally that no one is above the law and no individual is greater than the whole.

That it became instead, a place for our fellow Americans to once again declare their undying allegiance to this man, and to an ugly, lumbering, violent march toward an ever-deepening bottom is one of the absolute most tragic realities of my lifetime.

Now, the engineer of this delayed but now completed insurrection has no limitations on his sociopathy.

Donald Trump’s biography may well end with “…and dismantled 250 years of American democracy.”

Helpful Acting Advice for Performing ‘To Be Or Not To Be’ ⚙︎

Ten years on, and still funny. From the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2016 Shakespeare Live! celebration for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

(Sadly, in the U.S. I can find only paid options to watch the full two-hour show: Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video (affiliate links). It’s available on BBC iPlayer for viewers within the U.K. Everyone else would need to jump through several VPN and registration hoops and face the wrath of the BBC TV license authority.)

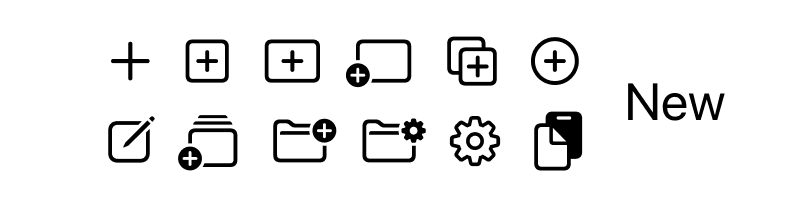

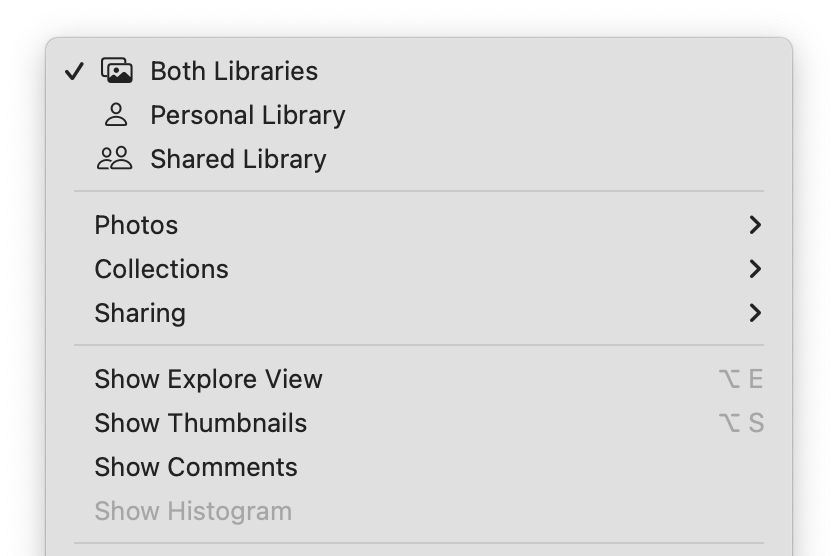

Nikita Prokopov on Tahoe’s Menu Icons ⚙︎

Nikita Prokopov, after reading the Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines from 1992 (“Don’t … overload the user with complex icons”):

Fast forward to 2025. Apple releases macOS Tahoe. Main attraction? Adding unpleasant, distracting, illegible, messy, cluttered, confusing, frustrating icons (their words, not mine!) to every menu item: It’s bad. But why exactly is it bad? Let’s delve into it!

Prokopov catalogues in tremendous detail the myriad ways macOS 26 Tahoe’s use of icons is inconsistent, confusing, and downright maddening. For example, Prokopov identifies twelve different icons for a “New” menu item.

It’s a brutal and well-deserved takedown.

My take is that the icon inconsistency is clearly iOS-inspired, where (virtually) all menu items have an associated icon, and seemingly stems from an apparent remand that all macOS menu items should also have icons for “consistency,” as if someone decided that consistency across operating systems was more important than decades of Macintosh user interface design—despite the current HIG explicitly stating “Not all menu items need an icon.” (It’s easy! Just pick one of the thousands of icons we’ve already designed! I can imagine that someone saying.)

I’m still running macOS Sequoia 15.5 on my main MacBook Air which—with few exceptions—doesn’t use icons in menus, and I’ve never once felt I was missing out.

With few exceptions (Safari, Messages, Photos, for example) macOS Sequoia doesn’t use icons in menus.

(I have no plans to “upgrade” this system to macOS 26 Tahoe unless it becomes untenable. I use Tahoe on a test system. It’s… painful.)

I hold out hope that someone at Apple sees this icon transgression and is humble enough to fix it.

Update: Unrelated, but the snowfall effect on Prokopov’s article made it difficult to read and caused my iPhone 17 Pro to heat up to the point of being hard to hold. Disabling the snowfall also swapped an otherwise readable blue background with a garish yellow one. Every creative has their unmurdered darlings.

‘ICE Accidentally Sends Maduro Back to Venezuela’ ⚙︎

Dan Rice at The Hard Times:

In a stunning instance of miscommunication between departments, ICE agents have deported Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro back to Venezuela just hours after he was abducted by the DEA.

Remember, in this timeline, “satire” is just something that hasn’t happened yet.

See Also: “Trump Is Boasting About an Alleged Land Strike in Venezuela — Here’s Why He Is Still a Pedophile”:

A regime change in Venezuela will not erase Trump’s relationship with sex trafficker Jefferey Epstein

It’s an open secret that Trump’s real goal here is to oust Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, a known dictator who just so happens to be sitting on some significant oil and rare earth mineral reserves. It is, however, also an open secret that Donald Trump bonded with Jefferey Epstein over their shared love of coercing sex from women under the age of 18. Trump himself has called this a “Wonderful secret.”

Jeffrey, but still: The Hard Times goes hard.

‘How the US captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro’ ⚙︎

Meg Kinnard and Michelle L. Price, writing for AP News:

Months of covert planning led to the brazen operation overnight, when President Donald Trump gave an order authorizing Maduro’s capture. The U.S. plunged the South American country’s capital into darkness, infiltrated Maduro’s home and whisked him to the United States, where the Trump administration planned to put him on trial.

Months of planning.

Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at Trump’s news conference that U.S. forces had rehearsed their maneuvers for months, learning everything about Maduro — where he was at certain hours as well as details of his pets and the clothes he wore. […]

Rehearsed for months.

Trump said on Fox that U.S. forces had practiced their extraction on a replica building.

“They actually built a house which was identical to the one they went into with all the same, all that steel all over the place,” Trump said.

Built a house.

I don’t know how long it takes to build a replica of a heavily fortified presidential compound, but I’ll guess it’s not a short period of time.

I’m left wondering exactly when this operation “Absolute Resolve” was initially broached, and whether the attacks on alleged “drug-carrying” boats off the coast of Venezuela, which started in September and have killed at least 115 people, were mere pretext and distraction.