Fast, private email that's just for you. Try Fastmail free for up to 30 days.

Garrett Graff: ‘Three Reasons I Still Have Hope for America’

Garrett Graff: ‘Three Reasons I Still Have Hope for America’

This optimistic piece from Garrett Graff comes as we head into this weekend’s No King’s protest:

To me — as someone who cares deeply about the future of American democracy — the rallies stand as an important expression of love for the United States and the idea and dream that the US has represented for 250 years.

Graff has been writing about how the United States has tipped into authoritarianism, but offers “three significant reservoirs of hope”:

1. People — There are more of us than there are of them.

It’s easy to lose sight of how weak this administration’s popular support actually is. Two-thirds of Americans are not Trump voters — and even many who did support him are beginning to question or turn against what it’s like to live in Donald Trump’s America.

2. History — America’s progress has always been imperfect.

Ironically, the second pillar of hope I have is that the history of the United States is filled with dark chapters — sometimes, even long dark chapters.

We are a country founded on a deeply imperfect premise, “all men are created equal,” that at that time excluded enslaved Blacks, women, indigenous people, and even white men who didn’t own property. America has many stories and the one that I choose to believe is the one where we are a country that strives, generation by generation, decade by decade, to be better. That viewed across 250 years, America is a country where each generation has strived to hand off a country more just, equal, and prosperous than the one they inherited from their parents and grandparents.

3. Actuarial — Trump won’t last forever, which means “Trumpism” will fall.

Trump may want to be a dictator and emulate Franco and Orban, and — who knows — maybe the ridiculous White House ballroom he’s building is an indication he doesn’t plan to leave peacefully on January 20, 2029, but time tells us that he’s never going to be Franco, the dictator who reigned in Spain from 1939 until 1975. The reality is Donald Trump is 79 and not well — and probably less well than the media is willing to dig into — and his reign as president and America’s would-be king will be measured in years, not decades.

Whenever and however Donald Trump exits the stage, there just isn’t anyone who will step into the MAGA movement’s shoes — there are plenty of people who will try, from JD Vance to Marco Rubio to Ron DeSantis to Don Jr. to Ted Cruz, but the thing we’ve seen over and over across the last decade is that no one is Donald Trump. Vice President JD Vance, an incredibly awkward and unfunny Trump-lite who is widely despised by both sides, is most certainly not Donald Trump.

It’s a welcome piece—long, but detailed. If you’re looking for nuggests of hope, you might find them here.

If you’re attending a No Kings protest on Saturday, stay safe.

Apple is Now the Exclusive Formula 1 Broadcast Partner in U.S.

Apple and Formula 1® today announced a five-year partnership that will bring all F1 races exclusively to Apple TV in the United States beginning next year. […]

Apple TV will deliver comprehensive coverage of Formula 1, with all practice, qualifying, Sprint sessions, and Grands Prix available to Apple TV subscribers. Select races and all practice sessions will also be available for free in the Apple TV app throughout the course of the season. In addition to broadcasting Formula 1 on Apple TV, Apple will amplify the sport across Apple News, Apple Maps, Apple Music, and Apple Fitness+. Apple Sports — the free app for iPhone — will feature live updates for every qualifying, Sprint, and race for each Grand Prix across the season, with real-time leaderboards, season driver and constructor standings, Live Activities to follow on the Lock Screen, and a designated widget for the iPhone Home Screen.

According to emails sent to current Formula 1 TV subscribers, F1 is keeping its “F1 TV Access” (the lowest-tier option—$3.49 a month or $29.99 a year, which does not include any live video streaming) and is phasing out its “F1 TV Pro” package ($10.99 a month) while shifting its highest “F1 TV Premium” tier ($16.99 a month—the “Ultimate F1 Live Immersion” which includes multiview and 4K streaming) to Apple TV:

From January 2026, our new Formula 1 broadcast partner in the US will be Apple TV. Next season F1® TV Premium will continue to be available in the U.S., included with an Apple TV subscription only.

You will still be able to purchase F1® TV Access, which remains available in the US.

Apple TV customers pay $12.99 a month and will now get that $16.99-a-month “Premium” tier as part of their subscription. That’s a hell of a deal. A lot more people might find themselves watching F1 races out of mere curiosity. I’ve never watched a single F1 race (or Drive to Survive or F1 The Movie), but this new partnership may finally get me to check out the hype, seeing as it’s now effectively free for me to do so.

Meanwhile, “F1 TV Pro” subscribers get full access to everything Apple TV has to offer for an extra $2 a month, while “F1 TV Premium” subscribers save $4 a month.

This seems like a massive win for everyone.

Additional information — including production details, product enhancements, and all the ways fans will be able to enjoy F1 content across Apple products and services — will be announced in the coming months.

I assume this will include an immersive Apple Vision Pro experience. An app called Lapz was briefly available and was considered the best way to watch F1 races. The F1 folks put the kibosh on it last year; perhaps one of them will acquire it.

One sour note, from the aforequoted press release:

Apple will amplify the sport across Apple News, Apple Maps, Apple Music, and Apple Fitness+.

Translation: We need to recoup our money somehow, so prepare to see a lot of unwanted F1 content. I can see it now: Your commute will take 45 minutes, but an F1® car would get you there in just ten. Subscribe to Apple TV to experience the thrill of speed.

‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show’ 50th Anniversary Collectible Steelbook

Yours truly, back in August:

[…] bless my soul, as sure as there’s a light over at the Frankenstein place, you can bet I’ll be buying the 50th Anniversary 4K edition when it’s released in October.

It’s released, ordered, and should arrive today. It’ll make a perfect weekend watch. (As always, Amazon links can earn me a couple of pennies. Time is fleeting.)

‘I Replaced My Toaster’s Firmware and Now I’m a Fugitive’

I thoroughly enjoyed this short story by Jason Self. It’s a pitch-perfect future-tech satire that’s increasingly recognizable in our connected-everything/right-to-repair/DRM-and-subscriptions-everywhere reality:

My OmniHome™ SynapseToaster™, a sleek obsidian slab that cost more than my first car, was perfectly capable of producing golden-brown perfection. That capability was locked behind DRM. A notification would slide gracefully onto my OmniTab™ screen every morning: “Experience the Maillard reaction as our chefs intended. Upgrade to the Artisan Browning™ subscription for just 10 credits a month.”

I found it utterly delightful.

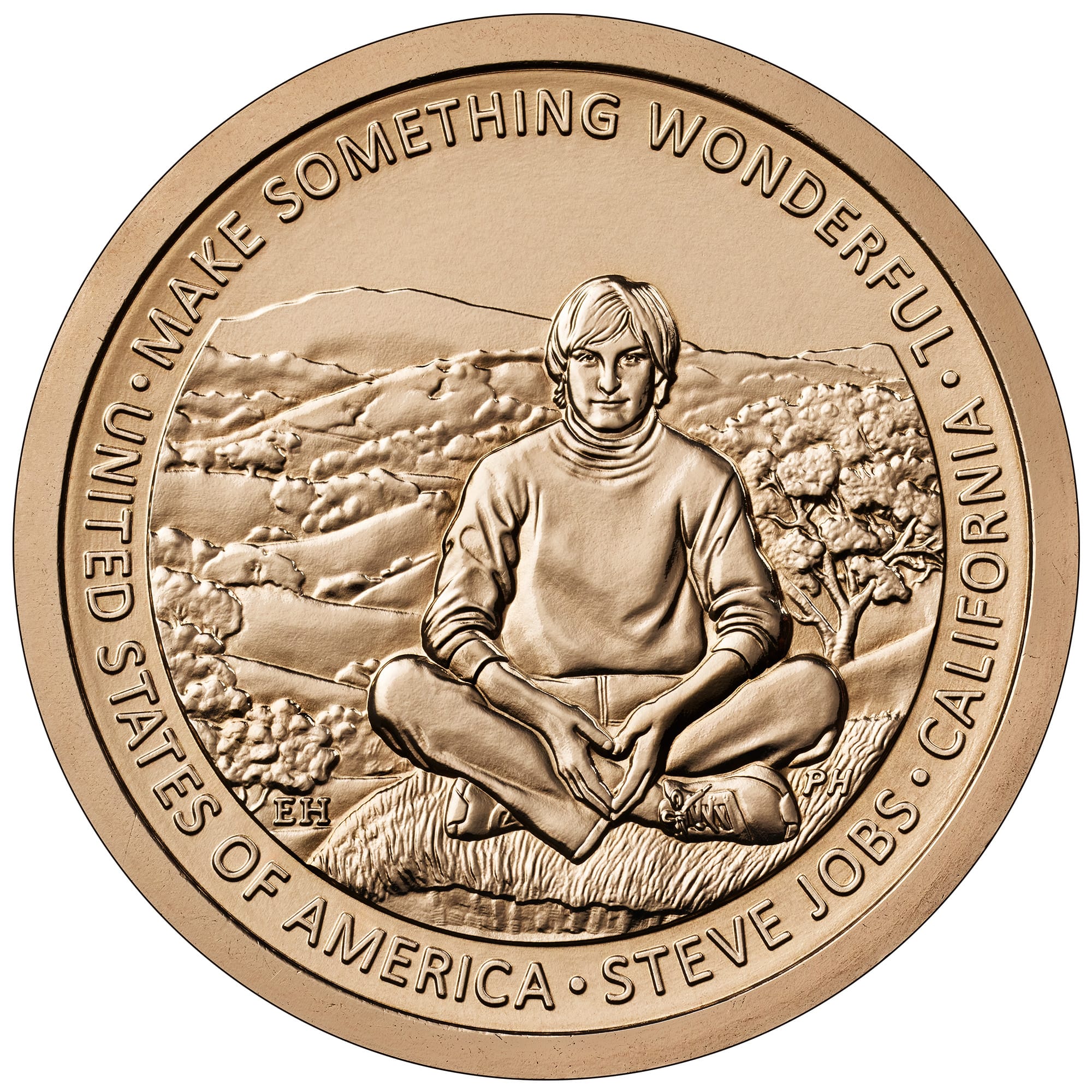

Official Steve Jobs $1 ’American Innovation’ Coin Design Revealed

The United States Mint (Mint) today released the designs for the 2026 American Innovation $1 Coin Program. The 2026 designs honor innovations and/or innovators from Iowa, Wisconsin, California, and Minnesota.

The California design features Steve Jobs:

This design presents a young Steve Jobs sitting in front of a quintessentially northern California landscape of oak-covered rolling hills. His posture and expression, as he is captured in a moment of reflection, show how this environment inspired his vision to transform complex technology into something as intuitive and organic as nature itself. Inscriptions are “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA” and “CALIFORNIA.” Additional inscriptions are “STEVE JOBS” and “MAKE SOMETHING WONDERFUL.”

This is the design recommended by Governor Gavin Newsom earlier this year. It doesn’t exactly scream California innovation! to me, though—perhaps it needs a Macintosh in Steve’s lap.

(This is not the design the Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee preferred, which featured Steve as older and wearing glasses and a turtleneck. That design, while certainly a more familiar image, placed even greater emphasis on the man. This design at least alludes to California as a source of inspiration.)

The $1 coins will sell for $13.25 each.

Apple Debuts M5 in Refreshed MacBook Pro, iPad Pro, Vision Pro

In a series of press releases, and as teased by Joz yesterday, Apple announced a faster M5 chip and three updated products to leverage its power. Apple Newsroom links:

These are welcome spec bumps, but nothing truly earth-shattering here—simply faster, more capable hardware year over year. If you have an M4-based device, you’re unlikely to be tempted unless seconds lost equals money lost. For earlier hardware, especially M1- and Intel-based devices, these represent significant upgrades.

M5

The new M5 chip is built on “third-generation 3-nanometer technology,” and improves unified memory bandwidth to 153GB/s (“a nearly 30 percent increase over M4 and more than 2x over M1”). It’s notably faster than the M4 and earlier M-series chips, with Apple touting its improved performance for AI, gaming, and 3D applications. It’s a beast—and probably overkill for most people.

Apple Vision Pro

The updated Apple Vision Pro with M5 offers “improved display rendering, faster AI-powered workflows, and extended battery life.” It now comes with a redesigned “Dual Knit Band” that is remarkably similar in concept to the 3D-printed solution I and many other Vision Pro users have been sporting. Also included in the box is Apple’s new, descriptively named 40W Dynamic Power Adapter with 60W Max. Apple Vision Pro (M5) maintains its $3,499 starting price. Preorders start today and will be available in store on October 22.

One meaningful improvement the M5 brings:

With M5, Apple Vision Pro renders 10 percent more pixels on the custom micro-OLED displays compared to the previous generation, resulting in a sharper image with crisper text and more detailed visuals. Vision Pro can also increase the refresh rate up to 120Hz for reduced motion blur when users look at their physical surroundings, and an even smoother experience when using Mac Virtual Display.

Sharper images and reduced motion blur are reasons enough for many current Vision Pro customers to consider upgrading—yours truly included—but Apple does not offer any trade-in options for Apple Vision Pro, making it a nonstarter for most of us.

(I was unrealistically hoping for a trade-in program that would take back my original Vision Pro for something close to full credit, as a thank-you for effectively acting as a beta tester. Preposterous, I know, but no trade-in options seems like a missed opportunity to recapture early adopters.)

The M5 also brings small improvements to battery life (“up to two and a half hours of general use, and up to three hours of video playback”) and performance (“up to 2x faster for third-party apps”).

Apple claims “over 1 million apps” are available for Apple Vision Pro, with “more than 3,000 apps built for visionOS.” I’ll be honest: it doesn’t feel like that many visionOS apps are available.

I also found this plug amusing:

And pro users can assemble and rehearse their presentations while in a seat-for-seat replica of the Steve Jobs Theater at Apple Park using Keynote.

That’ll be the closest most of us will ever get to trodding that stage.

MacBook Pro 14"

Apple is pushing the MacBook Pro 14"—unsurprisingly—as an AI system. I counted 24 mentions of “AI,” “Neural Engine/Accelerator,” or “LLM.”

The new hardware has “2x faster SSD,” “up to 4TB of storage,” “1.6x faster graphics performance,” “up to 20 percent faster multithreaded performance,” and “24 hours of battery life.”

Sadly, no teal—space black and silver only, again. MacBook Pro 14" (M5) can be preordered today at a starting price of $1,599. Available October 22.

iPad Pro

For many people, this new M5-powered iPad Pro, running iPadOS 26 and connected to a 4K display and keyboard, is all the computer they’ll need.

The iPad Pro can now drive external displays at up to 120Hz, with support for Adaptive Sync for “the lowest possible latency.” It now has the Apple-designed C1X modem and N1 networking chip (which combines Wi-Fi 7, Bluetooth 6, and Thread). Storage is twice as fast, and the 256GB and 512GB models come with 12GB of high-bandwidth memory (up from 8GB in the M4), while the 1TB and 2TB still contain 16GB. The new iPad Pro also adds fast charging (up to 50% charge in 35 minutes) with a capable charger. Pricing for the 11" iPad Pro starts at $999 for Wi-Fi and $1,199 for Wi-Fi + Cellular, and the 13" iPad Pro starts at $1,299 (Wi-Fi) and $1,499 (Wi-Fi + Cellular). And yes, preorders start today and will be available in stores on October 22.

Joz, Apple’s Marketing Chief, Teases M5 MacBook Pro

Greg Joswiak, Apple’s Senior VP of Marketing, posting to X/Twitter (link is to xcancel.com, so you can safely click without actually visiting the hellsite):

Mmmmm… something powerful is coming.

After years of “we don’t even wink in the direction of new products,” it’s weird to see Apple executives actively teasing new products.

It doesn’t take a marketing genius to figure out five “M”s equals “M5”. The Roman-numeral-V-shaped silhouette of the included video simply rams it home:

The headphone port on the left aligns with a MacBook Pro (not Air). And this may be just the lighting, but it looks a smidge thinner. Plus—and perhaps this is merely wishful thinking—the overall coloration, and the closing Apple logo, implies the tantalizing possibility of a MacBook Pro in something other than Space Black or Silver.

Not that I’m in the market for a new MacBook Pro.

A new MacBook Air with cellular though….

Drew Struzan, Iconic Artist Behind ‘Star Wars’ and Other Classic Movie Posters, Dies at 78

Drew Taylor, The Wrap:

Drew Struzan, the poster artist behind “Star Wars,” “Blade Runner,” “The Thing,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Back to the Future” and countless others, died on Tuesday due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease, his family said on a statement. He was 78.

I didn’t know the artist, but I sure as hell knew the art. If you love movies, you most assuredly know Struzan’s work, too. For many of us, his posters are the defining image for that movie. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Return of the Jedi, Back to the Future, Coming to America, and more of Struzan’s iconic posters are all indelibly imprinted on my brain.

RIP to a legend.

(Via @andhow by way of @raganwald.)

Help Find a Cure for Type 1 Diabetes (T1D)

Yours truly, last year:

I’ve known Kira, the daughter of my good friends Ron and Irene Lue-Sang, since she was a day old. She was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) nearly a decade ago. Since 2015, the Lue-Sang family have helped raise funds to end T1D by walking in the annual Breakthrough T1D Walk (formerly JDRF).

It’s no longer “nearly,” notes the family:

This is a milestone year. Kira has been living with Type 1 Diabetes for 10 years.

Kira’s off to college next year. I’ve watched her grow from a rambunctious girl into a beautiful, smart, thoughtful, and talented young woman. She hasn’t allowed T1D to slow her down one iota.

As they have every year since Kira’s diagnosis, the Lue-Sangs are again raising funds as part of their “commitment to do whatever we can to help develop new treatments—and ultimately a cure—for this currently incurable disease.” They’ll participate in the Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF) Walk on Sunday, October 19, 2025.

They’ve set a public goal of raising $5,000, and they’re about 70 percent of the way. I’d like to see them achieve it, so I’m doing a donation match challenge this year. I’ll match, dollar-for-dollar, any donations you make to the Lue-Sang T1D team between now and October 18, 2025 (the Saturday before the Walk), up to $1,000. You donate $5, I match your $5—doubling our impact. Just point me to your name on the team leaderboard or send me a screenshot showing your donation (redact any sensitive info, please!). Prefer to remain anonymous? Use “Kira’s Match” as the “Recognition Name” when completing the form.

I recommend donating to a specific walker on the team. Once a walker reaches specific fundraising levels, they’re granted “V1P” status, which awards them with a variety of swag and grants them access to a “special V1P lounge for an exclusive celebration experience.”

(Kira has already achieved V1P status, so I’m directing my donations to Kira’s sister, Tyrine, so they can enjoy the V1P experience together.)

Your donations help fund the research and scientific breakthroughs for T1D treatments and bring us closer to a cure. Last year, Ron told me:

One hundred years ago, science had barely discovered insulin. Before that, people with Type 1 Diabetes just wasted away a few months or years after diagnosis.

Ten years ago our standard of care was pricking Kira’s fingers to check blood sugar levels at least four times a day and injecting insulin by hand. We’re grateful for the advances technology has brought, including modern insulin, continuous glucose monitors, and insulin pumps. But we believe—it’s an article of faith—that there are still more advances to come, if only we pursue them.

Contributing to Breakthrough T1D helps them pursue those advances. Any amount helps, whether it’s $5, $10, or $100. And this year, your contribution will have double the impact.

Once again, the Lue-Sang family thanks you, and I thank you.

Republicans’ Government Shutdown Cancels Blue Angels for SF Fleet Week

This year, the high-flying Blue Angels were not the highlight of San Francisco Fleet Week, held this weekend, noted NBC Bay Area:

It’s official. The U.S. Navy, including the Blue Angels, will not participate in San Francisco Fleet Week this year due to the ongoing federal government shutdown.

In a statement late Tuesday night, the San Francisco Fleet Week Association said U.S. Navy ships, Sailors, and Marines would not take part in this year’s events “due to the continuing lapse in federal appropriations.”

The Republican government shutdown grounded America’s aerial acrobats. Thank goodness for the Canadian Snowbirds, eh?

Perhaps the Qatari Air Force can perform next year.

In addition to dashing away the innocent joy of watching the Blue Angels fly jet planes in precise, death-defying formation, the Republican shutdown also means furloughing 34,000 IRS employees, the closure of National Parks, an expected explosion of healthcare costs, and less safe airports as TSA agents and air traffic controllers worry about their next paycheck. Oh, and Donald Trump suggests those federal workers don’t deserve back pay.

🎶 America, America… 🎶

Disappointing Dozens of Customers, Apple Clips is No More

The Clips app is no longer being updated, and will no longer be available for download for new users as of October 10, 2025. You can continue to use Clips on iOS 26 and iPadOS 26 or earlier.

The app is no longer shown under Apple’s App Store listing , and visiting the link returns an “App Not Available” or “Cannot Connect” error.

Apple introduced Clips in 2017 without much fanfare as a “fun, new way to create expressive videos on iOS,” but it failed to catch on with the Instagram and TikTok crowd. The app received just a handful of updates in subsequent years and had long been presumed dead, baby. Now it’s official: Clips has ceased to be. It is an ex-app.

A Bookmarklet for Creating Text Fragments

When linking to sites, I’ve often wished I could link directly to specific text on a page rather than the page itself. Earlier this year, I learned this was possible by using Text fragments. Quoting from that MDN link:

Text fragments link directly to specific text in a web page, without requiring the page author to add an ID. They use a special syntax in the URL fragment. This feature lets you create deep links to content that you don’t control and may not have IDs associated. It also makes sharing links more useful by directly pointing others to specific words.

Text fragments have been a feature of several browsers since 2020 and came to Safari 16.1 in 2022.

A text fragment link contains four parameters, three of them optional:

https://example.com#:~:text=[prefix-,]textStart[,textEnd][,-suffix]

The only required parameter is textStart; this text will be highlighted on the page. For example, to link to the word “Scarborough” in my Naming My Devices article, you would add #:~:text=scarborough to the end of the URL:

https://jagsworkshop.com/2025/08/naming-my-devices/#:~:text=scarborough

(You can click that link to try it.)

The text must be percent-encoded—meaning spaces and most punctuation must be replaced by their hex values; for example, a space is %20. That’s simple enough for a word or two, but I usually link to a sentence, or sometimes an entire paragraph. Here’s an example that links to the phrase “1) New York Mets vs. Boston Red Sox: 1986 World Series” which percent-encodes the ), :, and each space:

This can be shortened by adding textEnd to give a start and end point to highlight; here, start with “1)” and end with “Series”:

(From my tribute to Davey Johnson.)

You can see the format is relatively easy to understand, but finicky. Trying to do this by hand would be madness.

So I built a JavaScript bookmarklet to do it.

Bookmarklets

Bookmarklets are like regular web browser bookmarks, but instead of saving a link to a website, they store JavaScript that the browser executes when selected. They can even include CSS and load external resources. Virtually anything you can do with regular JavaScript you can do with a bookmarklet. Yes—including playing Doom.

This bookmarklet started as just a single dialog box that accepted a text entry, which was then percent-encoded and copied to the clipboard. It evolved into a more complex custom overlay that accepts all four components of a text fragment, copies the encoded URL to the clipboard, opens it in a window for verification, and properly handles Escape and Return keys to activate the Cancel and Generate buttons. It’s nicely styled, and it even places keyboard focus in the first field to make basic use as simple as: invoke, type, return.

Try it here: Drag this link to your bookmarks bar, name it, then click the bookmark.

Here’s a Gist for the code. It consists of two parts:

- The first line of the Gist is a comment with the minified and percent-encoded JavaScript code that’s copied into the bookmarklet: copy everything starting with

javascript:(remove the leading//) and paste it into a bookmark. - The remaining code is the un-minified version, for ease of reading and editing.

(I borrowed the idea for this structure from John Gruber.)

Let me be clear about this code: I am very much not a JavaScript programmer. I know my way around the syntax, can edit existing code well enough, and can write basic functionality—but that’s about it. Anything more complex and I rely on the kindness of internet strangers. Or, increasingly, on Anthropic’s Claude, which knows JavaScript much better than I do and can synthesize often contradictory suggestions into a single, comprehensive (though sometimes wrong!) answer. Thanks to Claude, I was able to scrape this bookmarklet together without spending hours banging my head against a wall. Is it the most efficient or the best way to do this? Most assuredly not! But it works great for my needs. Maybe it does for yours, too.

(If you have any suggestions for improvements, please let me know.)

Adding and Using the Bookmarklet

To set up the bookmarklet:

- In your browser of choice, create a new bookmark.

- Copy the minified JavaScript (the first line of the Gist, without the

//). - Paste the JavaScript as the URL of your bookmark.

- Name it appropriately (I call it “TextFragment”) and save.

(If you dragged the test version to your bookmarks bar earlier, edit the existing bookmarklet and paste in the code from the Gist.)

To use the bookmarklet:

- Select the bookmark and complete the fields. See Text fragments for an explanation of each field. You must complete at least the

textStartfield. - Click Generate (or press Return/Enter). The page should load with the text highlighted, and the URL will be copied to the clipboard.

- Use the URL as you otherwise would.

Issues

I’ve seen three issues—two related to text fragments themselves, and one related to bookmarklets.

The first issue is that sites can opt out of text fragments (using Document-Policy: force-load-at-top) or remove anchors (anything after the # symbol). The second is that content can change, breaking your link. In each case, the link takes you to the top of the page, which is fine, but frustrating, as it loses the specific context you were trying to highlight, making the act of linking less effective. It’s not a deal breaker, of course—link rot is a reality of the web, alas. But it’s frustrating nonetheless.

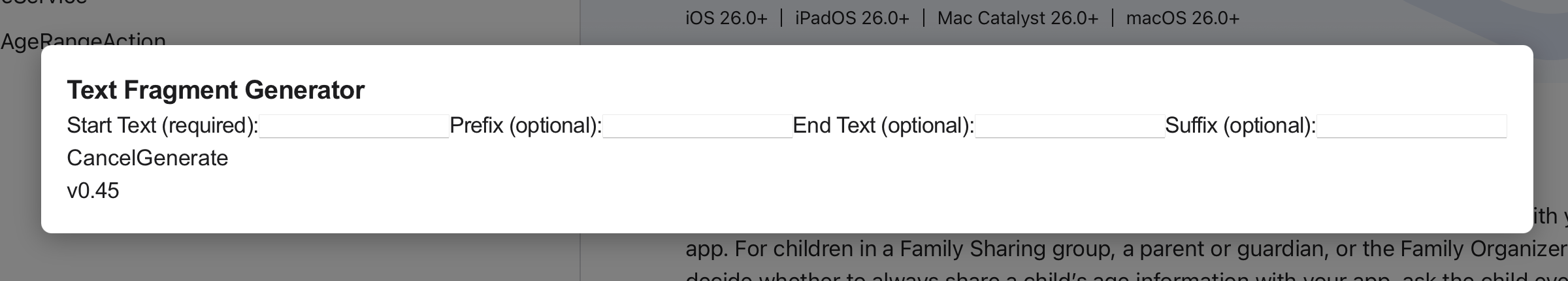

The more annoying issue is that some sites really mess with the overlay. Some, like ESPN, didn’t show the bookmarklet at all until I changed the z-index to the maximum (2147483647) so the overlay was above everything else on the site. Worse still, fonts, positioning, and sizing can all change depending on the CSS of the underlying site. While I’ve done what I can to isolate the bookmarklet styling, I still occasionally see changes. Most are minor, but some are pretty damn significant. Here’s what the overlay looks like on Apple’s Developer Documentation site, for example:

(Even more frustratingly, Apple Developer Documentation also strips anchors, so text fragments don’t work at all.)

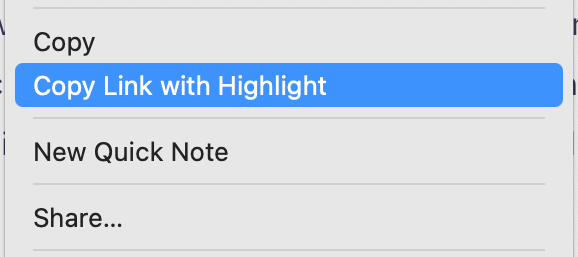

Postscript, or Learning Something New Every Day

After creating this bookmarklet and using it for a few days, I decided to look for other examples that do the same thing. It turns out there are dozens of examples of bookmarklets for creating text fragments.

In a double-turns-out, several web browsers even have a “Copy link with highlight” menu item that takes highlighted text and makes it into a text fragment link. (In Safari, it’s only available in the contextual menu accessed via a right- or control-click.)

I could be disappointed that I spent a few hours figuring out how to build this bookmarklet, but I very much subscribe to the philosophy of “I learn something new every day.”

Had I done my research prior to undertaking this exercise, I would have missed this opportunity to learn a little bit more JavaScript—including using CSS in a bookmarklet!—and I wouldn’t have further exercised Claude’s coding and troubleshooting abilities.

And, of course, I have a bookmarklet that works exactly the way I need it to, and can improve over time.

One “improvement” compared to most other solutions I saw: this version exposes all four text fragment fields, rather than just selecting the text you want to link to. This offers greater precision over what gets highlighted. For example, I can easily target a specific instance of a phrase that appears on a page multiple times, like selecting just the second instance of “Anthropic’s Claude” in my Blackmailing Claude piece, by filling in the -suffix field (“me”):

https://jagsworkshop.com/2025/05/how-long-ago-is-2900-weeks/#:~:text=anthropic’s%20claude,-me

Wanting that level of control may be the programmer in me, though, so one future improvement would be to use the current text selection to prefill the fields.

I’m off to experiment—before I learn someone already did this. In the meantime, let me know if this bookmarklet is useful for you.

Goodness, I love ‘Cards Against Humanity’

Cards Against Humanity has a new edition of its long-running deck of sometimes bawdy, generally silly, and always funny fill-in-the-blank cards they’re calling Cards Against Humanity Explains the Joke. The website opens thusly:

Trump is Going to Fuck Christmas

Like a teen girl at a beauty pageant, Christmas is in grave danger because of Donald Trump.

Via Nate Anderson at Ars Technica, who explains:

Cards Against Humanity, the often-vulgar card game, has launched a limited edition of its namesake product without any instructions and with a detailed explanation of each joke, “why it’s funny, and any relevant social, political, or historical context.”

Why? Because, produced in this form, “Cards Against Humanity Explains the Joke” is not a game at all, which would be subject to tariffs as the cards are produced overseas. Instead, the product is “information material” and thus not sanctionable under the law Trump has been using—and CAH says it has obtained a ruling to this effect from Customs and Border Patrol.

All of the profits, promises CAH, “go to the American Library Association to fight censorship.”

I noted the potential impact of tariffs on tabletop games when they were first announced in April (which feels like a lifetime ago). I love that CAH is trailblazing here, and supporting a good cause while they’re at it.

Preorders for Explains the Joke are $25 and close October 15. Oh, and it’s available only in the United States, because:

This is an American promotion for freedom-loving, tariff-hating Americans.

Ordered.

The Oatmeal on AI Art

Matthew Inman, AKA The Oatmeal:

I want to start with a simple observation:

When I consume art, it evokes a feeling. Good, bad, neutral—whatever.

When I consume AI art, it also evokes a feeling, Good, bad, neutral—whatever.

until I find out that it's Al art.

Then I feel deflated, grossed out, and maybe a little bit bored. […]

Even if you don't work in the arts, you have to admit you feel it too—that disappointment when you find out something is AI-generated.

Absolutely spot on. While I’m often impressed with the results of AI art, knowing that it took no artistic ability often leaves me cold. It has no heart, no emotion.

(Admittedly I often have a similar reaction to some modern art.)

Like Inman, I see some value in AI art (or AI coding or AI proofreading): as tools for eliminating drudge work (what Inman calls “administrative” rather than “creative” work) or for creating “throwaway” work that I wouldn’t otherwise spend time making. I might appreciate it, but I’m rarely inspired by it.

Apple Plays to IT Crowd with Strike at Blue Screen of Death

Apple’s favorite fictional team, The Underdogs, is back with an eight-minute ad—I’m sorry, short film—about the widespread, CrowdStrike-inflicted Windows Blue Screen of Death of 2024. Via The Verge, which describes it:

Apple’s ad follows The Underdogs, a fictional company that’s about to attend a trade show, before a PC outage causes chaos and a Blue Screen of Death shuts down machines at the convention. If it wasn’t clear Apple was mocking the infamous CrowdStrike incident, an IT expert appears in the middle of the ad and starts discussing kernel-level functionality, the core part of an operating system that has unrestricted access to system memory and hardware.

CrowdStrike’s Falcon protection software operates at the Kernel level, and a buggy update last year created BSOD issues that took down banks, airlines, TV broadcasters, and much more.

But not, of course, Macs, which were impervious to the assault.

The video was funny in the cringe way most of The Underdogs commercials are (they’re all a bit try-hard and need to improve their work-life integration), but it made the point: Macs are secure by default (and also have a bunch of time-saving features).

A couple of “production” notes:

- All five domain names on the business cards are registered (between April 15 and July 21, 2025), but none take you to a working site—not even a redirect.

- On the other hand, all the cards have a valid QR code that takes you to Apple at Work. Delightfully, instead of being printed on the cards, the QR codes appear to be physically cut-and-pasted on—exactly what you’d expect from companies unwilling to reprint their business cards.

- One domain not shown but can be inferred—that of our hero company, betterbag.com—does redirect to the same Apple at Work site. That domain was registered in September 2011. (Note: It’s not, as I mistakenly typed one time, betterbags.com—plural. That’s a real bag company. I wonder how they feel about the misdirected traffic.)

- At least one other fictional company, Origami Boxes, also uses Macs—you can see their hardware, and it’s still running.

- The “Credits” at the end describe the various security features (for example, Gatekeeper “Protects users from malicious software” and XProtect “Automatically detects and removes viruses and malware”), Apple hardware (Mac mini, Apple Watch) and software (Shazam, Genmoji, Find My), plus “special guests,” including Microsoft Excel and PowerPoint, JigSpace, Mailchimp, Myngly, Adobe Acrobat, Reddit, and Slack.

- Curiously, while Numbers makes an appearance, Pages and Keynote do not, which makes me wonder how they got their presentation up on screen—PowerPoint? Really, Apple?

New Raspberry Pi OS ‘Trixie’ Released

As long as I’m in the hacker space, I might as well mention the latest Raspberry Pi OS, named Trixie, which dropped last week. Simon Long writes on the Raspberry Pi blog:

We’re past summertime, and it’s an odd-numbered year, which means there is a new major release of Debian Linux, which in turn means there is a new major release of Raspberry Pi OS. This year’s version of Debian is called Trixie — as many of you know, Debian releases are named after characters in Disney’s Toy Story series of films, but all the well-known characters have already been used, so the names are getting increasingly obscure! Trixie is apparently a blue plastic triceratops who appears in Toy Story 3, but I must admit I can’t remember her — then again, I only watched that one once, because it got a bit sad towards the end…

I’m disappointed Long didn’t remember Trixie. She’s adorable, voiced by the very funny Kristen Schaal, and not at all obscure! He’s right about the sad, though.

But I digress.

Right. The release.

The biggest change: the Linux system clock, which was headed to its own Year-2000-style apocalypse in 2038, forestalls the issue by moving from a 32-bit number to a 64-bit number, so come 2038, the world (again) won’t collapse because of a date rollover—we now have until the year 292,277,026,596 to worry about that.

(You don’t remember Y2K? Kiss a programmer.)

There’s also a new desktop theme (new icons, new font, new desktop backgrounds; still ugly) and an updated “Control Centre” (yes, Raspberry Pi is based in the U.K.).

I haven’t had much need for my Raspberry Pis recently, thanks to Digital Ocean, but perhaps I’ll update them just to see how the new Trixie OS feels. It’s got to be better than macOS Tahoe 26, amirite?

Qualcomm Acquires Arduino

Qualcomm, on its acquisition of maker-focused Arduino for an undisclosed amount (via Emma Roth at The Verge):

Arduino will retain its independent brand, tools, and mission, while continuing to support a wide range of microcontrollers and microprocessors from multiple semiconductor providers as it enters this next chapter within the Qualcomm family. Following this acquisition, the 33M+ active users in the Arduino community will gain access to Qualcomm Technologies’ powerful technology stack and global reach. Entrepreneurs, businesses, tech professionals, students, educators, and hobbyists will be empowered to rapidly prototype and test new solutions, with a clear path to commercialization supported by Qualcomm Technologies’ advanced technologies and extensive partner ecosystem.

“Arduino” is practically synonymous with “DIY hacker projects,” and, I’ll admit, I still think of them as just the tiny microcontroller breadboard used by hobbyists to learn electronics and programming. The company closed a $22 million fundraising round two years ago, valuing them then at $54 million, which would be a rounding error at twice that for the $182 billion Qualcomm.

This seems like an unlikely pairing, making me skeptical this will end well for Arduino, but maybe it’s just an infusion of cash, and a chance for Qualcomm to sell more of its hardware to hobbyists and tinkerers while walking them up the enterprise ladder. Still, enshittification is real, and tiny companies have a way of quietly disappearing once acquired by behemoths. Crossing my fingers for Arduino and a generation of makers.

(Arduino also announced UNO Q, a $44 USD “dual-brain platform” powered by both a Qualcomm Dragonwing processor that runs Debian Linux and a realtime microcontroller, along with the free Arduino App Lab, “a brand-new integrated development environment that unifies the journey across real-time OS, Linux, Python, and AI.” I never got into the Arduino ecosystem—I was always a software guy, so I landed on the Raspberry Pi side of the divide—but this new kit and IDE have definitely caught my eye.)

‘Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish’: Steve Jobs’ Stanford Commencement Address, Twenty Years On

The Steve Jobs Archive has a wonderful digital exhibit about Steve Jobs’ Stanford address, which closes with the “Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish” quote I referenced in my remembrance:

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of Steve’s commencement address at Stanford, we are sharing a newly enhanced version of the video below and on YouTube. It is one of the most influential commencement addresses in history, watched over 120 million times, and reproduced in media and school curricula around the world.

If you’ve never seen the commencement address, you won’t regret the fifteen minutes. If you’ve seen it before, you already know it’s always worth revisiting. It’s an experience that stays with you.

Be sure to explore the related artifacts at the bottom of the page. They are equally wonderful.

A Dent in the Universe

Fourteen years ago today, Steve Jobs died. I wrote at the time:

It’s a sad day for me and for so many others inspired by Steve’s genius for products and marketing. It feels almost like a family member has gone.

That was no exaggeration. Steve had been part of my life in ways small and large since I was thirteen. It’s impossible to overstate the impact he (and the company he created, nurtured, and passionately led) had on me, my career, and my life. The first computer I ever used was an Apple II. My first “professional” job was Mac tech support for publishing houses. I spent twenty-two years inside Apple helping developers build apps for iPhone, Mac, and more. I met my wife and developed life-long friendships through Apple connections.

Without Steve, my life would be infinitely less.

It’s tempting, with Apple always in the news for their perceived lapses of leadership, to misuse this occasion to wonder, What would Steve do? That’s a fool’s game, of course: Steve was, to understate things, a complicated man. Sometimes a person’s public persona hides their private self. Sometimes we’re simply blinded by our parasocial relationships and want to believe we know someone because we’ve watched or listened to them for years. Sometimes, people simply change. We simply have no way of knowing who Steve would have become, or what he would have supported. We only know that while he was alive, and even after his death, he inspired millions of us to do things we never thought we could, to follow our heart and intuition, and to stay hungry, stay foolish.

For that, I’m grateful.

My first “encounter” with Steve came about a year after I’d started at Apple. As I steered my brand-new silver Nissan Altima off Highway 280 in Cupertino onto De Anza Blvd, a driver in a brand-new silver Mercedes SL 55 cut me off. I instinctively honked and cursed at him. I noticed then that the vehicle had no license plate—just what appeared to be a bar code where the plate would otherwise be. The driver turned onto Mariani Ave, then onto Infinite Loop, and into the parking lot in front of IL1. That’s when it all clicked: I’d just verbally flipped off my CEO. I desperately hoped he hadn’t seen me or recognized my car as I drove past him. I remained in a panic all day waiting for a call from HR stripping me of my badge for being so brusque. Fortunately, that call never came. I’m relieved Steve had more important things to focus on that day than an aggravated driver.

I did meet Steve, just once. It was as classic a moment as you could ask for. It happened not too long after he returned from his first medical leave of absence in 2009. I was boarding the elevator in Infinite Loop 1, where Steve’s office was, and as I pushed the button for my floor, I spotted him slowly ambling toward me. He appeared gaunt and tired. I briefly considered pretending I hadn’t seen him, but instead I held the elevator door while he made his way over. Smiling at him as he got on, I said, Glad to have you back. He thanked me, then asked the question I’d been both dreading and preparing for my entire Apple career: What do you do here? Fortunately, this was also not long after the introduction of a native SDK for iPhone and the launch of the App Store, so I was able to say proudly, I’m in Developer Relations, and I lead a team of engineers who help our third-party developers build world-class applications for iPhone. He nodded, noted how important that work was, and thanked me for doing it. Then, our ride was over. After he stepped off the elevator and the doors closed, I exhaled deeply. I’d managed to keep my job—but I’d missed my floor.

Kagi Launches a Free Daily Digest to Encourage a ’Healthy News Diet’

Kagi, the surveillance-free, paid search company, introduces Kagi News, a free news aggregation service:

Kagi News operates on a simple principle: understanding the world requires hearing from the world. Every day, our system reads thousands of community curated RSS feeds from publications across different viewpoints and perspectives. We then use AI to distill this massive information into one comprehensive daily briefing, while clearly citing sources.

Up to 12 stories in each user-selected category, published once per day at noon UTC.

Naturally, Kagi touts its privacy-focused design:

Your reading habits belong to you. We don’t track, profile, or monetize your attention. You remain the customer and not the product.

Kagi has also open sourced the web app and list of feeds that power the system.

After using it the last few days, I found many of the summaries useful, with helpful additional context, but several had a telltale smell of “AI.” For example, an “Apple” story headlined “MacOS Tahoe adds customization and Live Activities; Homebrew install tips” was an odd amalgam of barely related stories that made little sense together.

I’m not yet sure how Kagi News fits into my news consumption routine. I currently read dozens of RSS feeds every day and I can’t imagine being satisfied reading a handful of summarized stories instead. Beyond that, the selection of stories it features rarely matches my definition of “most important,” though it’s already exposed me to stories I might not have otherwise seen. It’s a promising idea, and I think it’ll be valuable to many people looking to curtail their news consumption, but it’s possible the entire concept of a “healthy news diet” is simply anathema to me.

Authoritarian Government Forces U.S. Companies To Remove Apps From Sale

You’d think, reading that headline, that the “government” in question would be Russia, China, or Hungary. You’d be wrong.

Apple has taken down an app that uses crowdsourcing to flag sightings of U.S. immigration agents after coming under pressure from the Trump administration.

ICEBlock, a free iPhone-only app that lets users anonymously report and monitor activity by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, was no longer available on Apple’s App Store as of Friday. The developer had confirmed its removal on Thursday evening.

CNBC:

Google on Friday joined Apple in removing from its online store apps that can be used to anonymously report sightings of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and other law-enforcement authorities.

Google’s statement (“ICEBlock was never available on Google Play, but we removed similar apps for violations of our policies”) is pure pablum, but Apple’s statement is unadulterated horseshit:

“We created the App Store to be a safe and trusted place to discover apps,” the company said in a statement. “Based on information we’ve received from law enforcement about the safety risks associated with ICEBlock, we have removed it and similar apps from the App Store.”

The opening phrase is stock Apple. They use it anytime they pull “undesirable” apps from the store. It’s what they said when they removed HKmap.live—a “crowdsourced reporting and mapping of police checkpoints, protest hotspots, and other information”—from the Hong Kong App Store in 2019, for example.

But the rest of it? I’m deeply skeptical. What information? Which law enforcement? What safety risks?

Is using ICEBlock to report the location of ICE agents any different from using a social media app to report the same information? Does reporting the location of police, FBI, or other law enforcement also pose “safety risks”? Unless Apple (or this regime) presents credible evidence the app led to violence, the reasoning behind pulling the app is bullshit.

(And by “credible,” I don’t mean allegations from Bondi that “ICEBlock is designed to put ICE agents at risk”—it’s not—nor implications that the recent shooter at a Dallas ICE facility used this or other apps to identify his target. Both are speculation without evidence.)

The message the ICEBlock developer received from Apple said the app was removed for “objectionable content.” Apple’s guidelines against “objectionable content” state:

1.1 Objectionable Content

Apps should not include content that is offensive, insensitive, upsetting, intended to disgust, in exceptionally poor taste, or just plain creepy.

What is offensive about identifying the presence of ICE patrols? Is it more disgusting to alert law-abiding Americans to take precautions than it is to watch them get snatched from their homes, work, and places of worship?

This is especially painful for me because I know and have worked closely with the teams and people who make these decisions. I’ve been in the room for debates about taking down apps. I’ve been on the calls when developers are informed of the decision to pull their app. Most takedowns have a reasonable justification.

This one has none.

The Trump regime has targeted ICEBlock since it launched. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi said then of the app developer:

He’s giving a message to criminals where our federal officers are. And he cannot do that. And we are looking at it, we are looking at him, and he better watch out, because that’s not a protected speech. That is threatening the lives of our law enforcement officers throughout this country.

Except, of course, it very much is protected speech.

In a statement to several news outlets, Bondi acknowledged governmental pressure on Apple, saying:

We reached out to Apple today demanding they remove the ICEBlock app from their App Store — and Apple did so.

“Demanding.” Not “requested.” Not “provided information about the safety risks.”

Demanding.

A demand from an Attorney General—especially the United States Attorney General—carries with it the weight of law. It implies legal consequences if the demand is not carried out.

What was Apple threatened with? Antitrust lawsuits? Tariffs? No more White House invites? A mean “Truth” Social screed?

Which law was the app violating that justifies the United States Attorney General demanding it be removed from the App Store?

Equally important, why is Apple complying with such a demand?

This isn’t the first time Apple has removed apps at the behest of authoritarian regimes. In addition to HKmap.live, mentioned above, Apple also pulled Russian voting app “Navalny” from the Russian App Store in 2021, and messaging apps like WhatsApp, Signal, and Telegram from the China App Store in 2024.

When Apple pulled those apps from China, it used another of its stock phrases that makes an appearance when it takes actions it deems legally necessary but morally repugnant: Apple is “obligated to follow the laws in the countries where we operate, even when we disagree.”

Apple used a similar phrase when it pulled TikTok from the App Store earlier this year: “Apple is obligated to follow the laws in the jurisdictions where it operates.”

(I’m forced to link to Internet Archive here because Apple has taken down its post, presumably after returning TikTok to the store upon receiving “presidential assurances.”)

Notably, Apple hasn’t used a similar phrase here, implying the decision to pull ICEBlock was based not on any violation of the law, but on a choice. An executive decision.

There’s a phrase that’s been making the rounds the last couple of weeks: Fuck you, make me. John Oliver suggested it in a recent Last Week Tonight episode (and John Gruber at Daring Fireball mentioned it today). It’s a valuable alternative to “don’t comply in advance” (which implies eventual compliance).

Why isn’t Apple standing up and saying Fuck you, make me?

(Or, in Apple-speak: After carefully evaluating the request of Attorney General Bondi, we’ve determined there is currently no legal basis by which we can comply with her suggestion. The app remains available for customers until a legal justification is presented for its removal.)

Instead, the app is removed without any pushback or meaningful explanation.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to argue that tech leaders like Tim Cook and Sundar Pichai, media moguls like Bob Iger and David Ellison, and the rest of the capitalist capitulators aren’t fully supportive of this fascist regime, and are happily “complying in advance” because it’s exactly what they want to do.

Apple’s apparent surrender, especially, is hard for me to swallow. After two decades on the inside, and two more before that as a fan, I’ve fully embraced Apple’s “dent in the universe” ethos. When Tim talks about Apple’s “North Star” or quotes Martin Luther King, Jr., I’ve always believed, with all my soul, that he meant it. It’s painful to criticize a company I’ve loved for most of my life, and which has benefited me immensely.

Apple has always claimed a higher moral ground. It proudly declares its Commitment to Human Rights, which starts:

We believe in the power of technology to empower and connect people around the world—and that business can and should be a force for good. Achieving that takes innovation, hard work, and a focus on serving others.

It also means leading with our values.

Apparently Apple’s values don’t include protecting people from fascist regimes.

National Writers Union on the Anthropic Settlement

As a follow-up to the Anthropic copyright settlement book search tool, here’s how the National Writers Union sees the settlement:

This is not the settlement that we as a union want, or that writers as creative workers deserve. But if writers do nothing, they may receive nothing, or less than they are entitled to. So in this moment, the NWU urges ALL writers to be proactive to see if their work is included and make claims for their full share of the settlement money – and to object if they think the settlement is unfair and should be rejected.

They are encouraging authors to register themselves with the settlement administrator, noting:

If you do nothing, you might get nothing at all. You might get a payment anyway, if your publisher tells the settlement administrator that you are entitled to a share, and if they can find you. But it could be less than you are entitled to.

There’s little reason for anyone to opt out except in the highly unlikely event that you are planning to bring your own separate lawsuit against Anthropic. (Good luck with that.) If you opt out, you will get no money from the settlement.

There’s a minute chance enough authors (and publishers) will object to the settlement that it doesn't go through. I’ll admit there’s a small part of me that hopes it blows up, mainly because I feel Anthropic is getting away with massive piracy for a pittance. You can be completely in the tank for AI and still want to see Anthropic (and OpenAI and Meta and …) fairly compensate the creators on whose works these AIs are trained. I suspect, though, that most authors will roll their eyes in contempt and begrudgingly accept these token payments rather than risk getting nothing.

A perfectly calibrated settlement.

Official Anthropic Copyright Settlement Book Lookup Tool Available

Now that the Anthropic settlement has received preliminary approval, authors can look up their books in an official tool. From the Anthropic Copyright Settlement site:

To see if your book is included in the settlement, select how you would like to search and enter your search terms.

You can search by ISBN/ASIN, Title, Author, or Publisher.

The search results differ from the search tool The Atlantic created. The site has an FAQ about that:

51. My work was on The Atlantic’s list of LibGen files. Why is it not on the Works List?

The Works List only includes works that meet the Class definition (as identified in FAQ 5). A work on The Atlantic’s list of LibGen files may not meet the Class definition for many reasons […]

Those reasons will disappoint many authors whose work was pirated, but which didn’t meet the criteria for compensation.

Clues by Sam

A new (to me) daily logic game where you “figure out who is criminal and who is innocent.” The clues are of the “There are more criminals than innocents to the right of Frank” and “There are exactly 2 innocents in row 3” variety. Each clue leads logically to the next, and there’s no guessing allowed: if the available clues don’t allow for a logical determination of a suspect’s innocence or criminality, you’re prevented from making that call. There is also, naturally, a Wordle-style “social media” component for sharing your results and time. Here are my results from today (I’d be much better at this if I wrote down the identified logic and built truth tables. Instead, I try to keep it all in my head, with the demonstrated slow results):

I solved the daily Clues by Sam (Oct 1st 2025) in less than 33 minutes

🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟨🟩🟨

https://cluesbysam.comI loved (and was pretty good at) these logic puzzles as a kid, and this one hurts my brain in exactly the right way. I find them much more enjoyable than Sudoku.

Ok, Fine, KPop Demon Hunters Is Great

And exactly what it says on the tin. This nine-minute trailer compilation will tell you quickly if this is your cup of ramen (“Beating you is what I do do do” is what hooked me). Gorgeous animation, vibrant characters, engaging story… oh yeah, and annoyingly infectious music. It comes by its three hundred million views honestly. Naturally a sequel and live action remake are in consideration. (Warning: spoilers abound in those links.)

Calendar Icon’s Lost Sentimentality

A few weeks ago, with the introduction of macOS 26 imminent, BasicAppleGuy published a collection of macOS icons from across its four-decade history:

With this release being one of the most dramatic visual overhauls of macOS’s design, I wanted to begin a collection chronicling the evolution of the system icons over the years.

I am a sentimental man, and this was a heck of a nostalgia trip for this “Apple Guy”: I’ve used every Mac operating system since the ’80s, and seeing some of these old icons brought back fond memories, especially the icons from the 1994–2001 era, which I consider my Macintosh “coming of age.”

The modern icons have certainly lost some of their charm, leading to (legitimate) gripes about icons that look like placeholders, but there was one that really stuck in my craw:

Calendar.

My bellyaching about the Calendar icon was initially based on late macOS 26 betas. That’s the last icon (“2025–”) shown in Basic Apple Guy’s Calendar collage: a small, abbreviated day (“Thu”) in red and a large date (“17”) in black, both over a cream gradient background. At first glance it could easily be mistaken for the previous icons.

But I had two issues with that new icon:

- It dropped “Jul”

- It replaced it with “Thu”

Even as the Calendar icon design morphed over the years, “Jul 17” remained. That date wasn’t chosen at random: it’s the date that Calendar—or more accurately, iCal, as it was then called—was first introduced: July 17, 2002.

It was a lovely little easter egg, an homage to its history, and a wonderful touch of humanity: a reminder that Apple is made up of people who care to include such details, as trifling as they may seem.

Apple’s product imagery is chock full of such easter eggs: iPhone and iPad time is always 9:41. Apple Watch time is always 10:09. And the Calendar icon was always July 17.

Now, this tiny touch of whimsy was gone from Calendar. Removing “Jul” from the icon throws away two decades of Apple history. It torches the goodwill of millions of long-time Mac users, and even new Mac users who might appreciate these little nods to nostalgia.

But wait, there’s more.

Why Thu in the revised icon? Was July 17, 2002 a Thursday and the new icon simply a more subtle reference to the release date? Let’s open Calendar, and jump back in time.

⇧⌘T 7 ⇥ 17 ⇥ 2002 ⏎

(For the non-Mac nerds, that’s Shift-Command-T to open Go to date; 7 tab, 17 tab, 2002; then press Return.)

Nope, July 17, 2002 was a Wednesday.

An Apple that paid attention to these details would have performed this basic check and used the right day to maintain a subtle connection to the icon’s past. Using “Thu” instead of “Wed” suggests the meaning behind the “Jul 17” date wasn’t fully understood.

I’ll be the first to acknowledge how trivial this complaint is, but much like reversing the colors of the Finder icon (since fixed) or the transparent-by-default menu bar, it’s another small sign that some at Apple don’t know—or care about—the history and traditions of Apple. Perhaps they aren’t even aware there is history and tradition to care about. It feels like we’re slowly seeing the death of sentimentality at a company that has historically embraced it. Is there anyone on the inside who still cares about these little subtleties and—crucially—is in a position of influence and authority to keep these flickers of fun alive? Phil? Joz?

With the release of macOS 26 came yet another Calendar icon. Gone is “Jul,” “Thu,” even the large “17.”

In its place is a red banner atop a cream background and an array of black dots representing days—and one red dot.

While I mourn the loss of “Jul 17,” and it’s not (by American standards) a July 2002 representation, I actually much prefer this newest icon over the “Thu” variant: it more directly harkens back to the earlier designs. (I’ll attribute the loss of text to efforts to be more international friendly.)

And that red dot? It marks the 17th day.

Now, I know I should be satisfied that some small sliver of sentimentality survives in the newest Calendar icon. But I can’t.

That red dot falls on a Thursday.

Why Every Mister Rogers’ Intro Theme Is Different

Yes, every intro of the nearly 900 episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was played live, but that’s not the reason—it’s because of improvisational jazz pianist Johnny Costa.

(I fell down @treehousedetective’s YouTube rabbit hole; his channel is filled with these surprising-yet-apparently-true nuggets. I highlighted this one because of its wholesomeness. Slightly less wholesome: why classic cartoon characters wear white gloves, why Mr. Snuffleupagus was finally revealed to adults, and why Doc and Marty were friends. I’ll never unknow these things.)

Jordan Mechner’s Favorite Version of ‘Prince of Persia’

Jordan Mechner, answering a question he gets a lot:

Which is your favorite/definitive version of the original Prince of Persia game?

He runs through the various versions, starting with the one I played incessantly:

The Apple II version was the original. It’s the only version I programmed myself; Prince of Persia’s gameplay, graphics, animation and music were all created on the Apple II. I spent three years sweating over every byte (from 1986 to 1989), so it’s close to my heart in a way no other version can be. That said...

I was surprised to learn the 1990 PC version is Mechner’s preferred variant:

If someone asked me the best way to play old-school PoP online today, I’d likely recommend the DOS version.

He calls the Mac port “terrific” (I, surprisingly, never played it). Of the Super Nintendo version, which I played the heck out of, Mechner wrote in his journal:

Wow! It was like a brand new game. For the first time I felt what it’s really like to play Prince of Persia, when you’re not the author and don’t already know by rote what’s lurking around every corner.

He called playing it a “delighted thrill.”

Mechner also makes passing reference to “Sands of Time,” which I played a lot on my PlayStation 2.

Thirty-five years on, I’m still playing Mechner’s game. Sitting on my PlayStation 5 right now is Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown.

The Athletic: What We Learned From MLB’s Spring Robot-Umpire Test

Jayson Stark, writing for The Athletic back in March, examined the results of MLB’s Spring Training test of the Automated Ball Strike (ABS) Challenge System that’s coming next year (main link is paywalled, sorry; here are Apple News+ and Internet Archive links):

Stark spoke with players, managers, and team executives to get their take on the system. My main takeaway is that the system works… for some definition of “works”:

Every hitter, catcher and pitcher has an idea in his head of what a strike is and what a ball is. So for ABS to work — really work — the electronic strike zone has to feel essentially like the zone baseball players have in their heads.

You know what won’t work? If that zone feels just like some sort of technological creation.

So which was it this spring? Uh, let’s just say it’s a work in progress.

Tigers catcher Jake Rogers, on reviewing the ABS results after games:

“It’s crazy,” Rogers said, “because on ABS, you look at the iPad … and (the pitch is) half an inch below the zone. And then we get our report back with the old strike zone, and it’s a full ball in the zone. So it’s like, wow, it looks like a strike. It feels like a strike. And all of a sudden, you’re thinking: Do you challenge, or do you not challenge? So you go back and look at it, and it’s a ball (on ABS).”

Journeyman pitcher, Max Scherzer:

In his recent appearance on the Starkville podcast with me and Doug Glanville, Scherzer said one thing he’d like to see is “a buffer zone, maybe around the challenge system. So hey, if you challenge and it’s in the buffer, the call stands. So you keep human power, the human element, still with the umpire.

“I’m OK changing the call when it’s an egregious call,” the Blue Jays’ future Hall of Famer said. “But when we’re talking about a quarter of an inch that you can’t really detect it, I don’t necessarily know if that makes the game better.”

I agree with Scherzer. It’s great to have the system to correct clearly wrong calls. I’m less enthused about relying on it to make a call based on fractions of an inch—which no human could reliably distinguish in the best of circumstances anyway. If an umpire calls a pitch a ball, and was “wrong” by an eighth of an inch, that’s not a bad call. It’s a human call, and baseball is still a human game.

Stark asks, ”Are we sure this is what we want?”

Do we really want a World Series decided by a pitch that’s literally the width of a hair off the plate? I asked that question of an AL exec. He swatted it away like a piece of lint.

“Maybe just get the call right,” he said.

Stark closes:

What’s the true goal here? What are we trying to accomplish?

Technology is awesome. Robots are the future. And right calls are better than wrong calls. But is the sport truly better off if a World Series gets decided on a pitch 1-78th of an inch outside a robotized strike zone? The answers are so much harder than the questions.

MLB Approves ‘Computer’ Umpires for Challenged Ball/Strike Calls

MLB, earlier this week:

Major League Baseball (MLB) today announced that the Automated Ball Strike (ABS) Challenge System has been approved for Major League play by a vote of the Joint Competition Committee. Beginning in 2026, the “Challenge System” will be used in all Spring Training, Championship Season, and Postseason games.

It looks like we’ll have computerized umpires regularly calling balls and strikes before we see a full-time female umpire in the game.

From the “How It Works” section of the announcement:

If a pitcher, catcher, or batter disagrees with the umpire’s initial call of ball or strike, he can request a challenge by immediately tapping on his hat or helmet and vocalizing a challenge. The pitch location is compared to the batter’s strike zone, and if any part of the ball touches any part of the strike zone, the pitch will be considered a strike. The home plate umpire will announce the challenge to the fans in the ballpark and a graphic showing the outcome of the challenge will be displayed on the scoreboard and broadcast. The entire process takes approximately 15 seconds.

The system’s been used at the Triple-A level since 2022, and at the Major League level during this year’s Spring Training and All-Star Game.

Baseball has always been a game of inches. Part of the joy and pain of the game is knowing that an inch here or an inch there can dramatically alter the outcome of an at-bat, a game, or a season. While egregiously bad calls deserve to be challenged and overturned, I’d hate to see the game become a contest of constantly challenged calls of balls and strikes. My love of baseball has already been strained under rule changes I detest. I’m hoping this won’t be one more reason for me to stop caring.

‘As I Was Saying Before I Was Interrupted’: Jimmy Kimmel Echoes Jack Paar in His Return

Jimmy Kimmel, returning to his show on Tuesday after his suspension over a pointed joke, quotes Jack Paar upon his return to The Tonight Show 65 years earlier, after walking off in protest over a censored joke.

Different circumstances, of course, but I appreciate that Kimmel (or his people) knows and respects the history of late night talk shows enough to make the reference.

Kimmel’s monologue (6+ million viewers on TV, 18+ million on YouTube) struck exactly the right tone of defiance, conciliation, and emotion. He choked up during his “apology” for last week’s joke, and followed it up with this:

This show is not important. What is important is we get to live in a country that allows us to have a show like this.

I’ve had the opportunity to meet and spend time with comedians and talk show hosts from Russia, countries in the Middle East, who told me they would get thrown in prison for making fun of those in power, and worse […]. They know how lucky we are here. Our freedom to speak is what they admire most about this country. And that’s something I’m embarrassed to say I took for granted until they pulled my friend Stephen off the air, and tried to coerce the affiliates who run our show in the cities that you live in to take my show off the air. That’s not legal, that’s not American, that’s un-American, and it’s so dangerous.

He went hard after Brendan Carr and Donald Trump, and took a dig at Disney while he was at it, reading a “statement” that was one of the “conditions” of his return:

To reactivate your Disney+ and Hulu account, open the Disney app on your smart TV or TV-connected device.

I’ve very rarely paid attention to Kimmel. I have no particular issue with him, beyond not finding him especially entertaining, but I’m glad to see he’s not backing down from this fight.

(Be sure to stick around for a very De Niro appearance by Robert De Niro.)

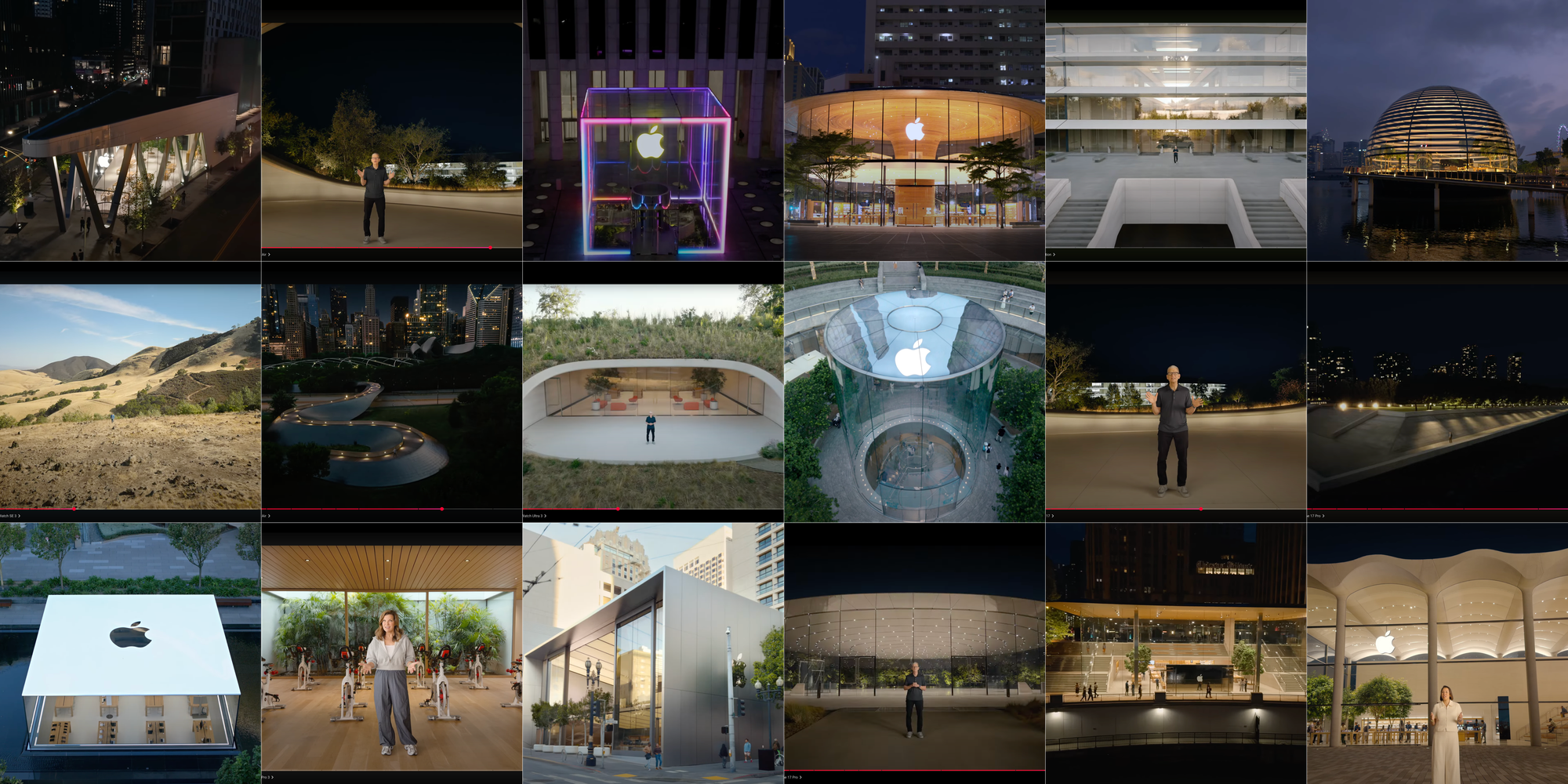

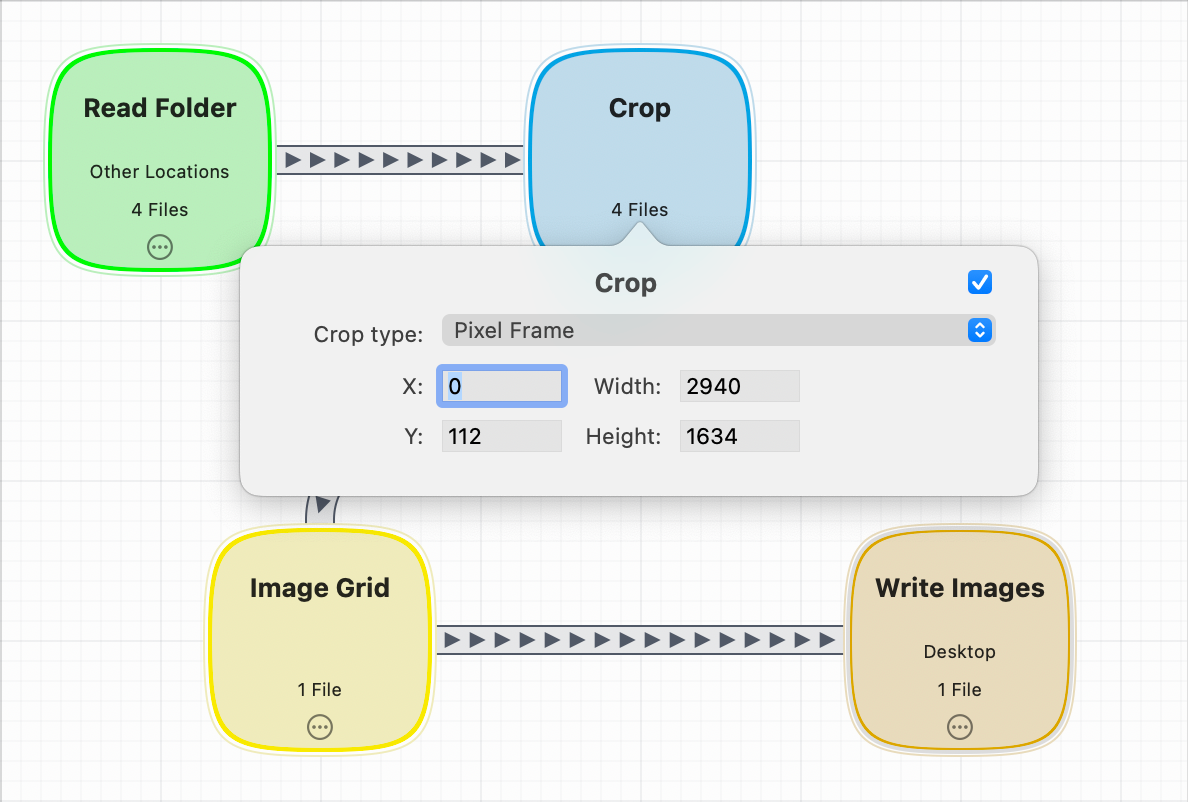

Apple Store (and More) Locations from September’s ‘Awe Dropping’ Event

It started with my question to a group of retired Apple friends as we watched the Apple September event:

I missed which Apple Store Kaiann is at; anyone know?

One friend guessed Dubai, suggesting the establishing shots “looked like the Middle East,” but I was doubtful Apple would fly one of its VPs to the Middle East for a short video shoot.

Besides, those opening shots kind of looked like Miami Beach to me, if I could trust my years of watching Miami Vice and Burn Notice. So I went through that segment again and spotted two landmarks: The Carlyle and the Leslie Hotel. A search in Maps confirmed those were in Miami Beach (yay TV!), and a check on Apple’s Find a Store page narrowed it down quickly to Apple Aventura.

Now I was curious: Could I identify all of the Apple stores shown in the video?

And just like that, a quest was born.

I expected it would be a chore—rewarding, but still. Finding Aventura involved scrubbing through that section of the video to identify landmarks, then combing through a list of possible stores until I found a matching photo.

As I was familiar with only a handful of Apple stores, and I wasn’t sure how many were shown during the event, it took a few days to properly motivate myself to do a full rewatch, dreading, as I was, the prospect of laboriously scrubbing through an hour-plus video, painstakingly identifying any tiny detail that would finally unlock the mystery of each location.

I needn’t have worried.

There were only a handful of stores Apple people spoke from. Some stores were gimmes. Others were either iconic enough or had easily discernible landmarks, making them (relatively) easy to find.

But the biggest reason this exercise was not the slog I anticipated was ChatGPT. In April, OpenAI released an update that added image analysis, giving ChatGPT the ability to deduce locations from images. I was impressed (and scared) by it then, and its performance here was remarkable, nailing 17 of 20 locations (85%) on the first try, and identifying the rest through extended prompting. (When it was wrong, though, it was hilariously wrong.)

Regardless of the ease or difficulty in finding the right store, once found, it was immediately identifiable: the architecture of each store was unique and unmistakable—and, of course, stunningly beautiful.

The process

The workflow for identifying locations was straightforward, if manual: I paused the video and took screenshots of each location, which I then fed into ChatGPT. For each location, I first tried using my own knowledge, plus landmark clues, to identify it.

There were four types of locations I identified (though I’d started this quest with only the first one in mind):

- Apple Store locations with presenters (five stores).

- Non-Apple Store locations with presenters (four spots).

- Apple Store locations in flyovers/beauty shots (seven stores).

- Apple Park locations (four locations).

I easily identified all of the Apple Park locations, having worked for several years in and around the campus. Likewise, I’ve spent countless hours at Apple Park Visitor Center in Cupertino and Union Square in San Francisco.

The Cube at Fifth Avenue is iconic, and the Chicago skyline and the Tribune building behind Michigan Avenue made that a quick find (I’ve also visited both).

(It turns out all of the Apple Store presentation locations were in major American cities: New York, San Francisco, Cupertino, Chicago, and Miami. Having seen those skylines or views hundreds of times helped narrow the field of search considerably.)

The flyovers and non-store locations were the toughest; I relied almost exclusively on ChatGPT here, validating each answer independently through online searches (including Apple’s Find a Store).

In some cases, ChatGPT identified stores confidently but incorrectly. Fortunately, it was easy enough to check and inform it when it was wrong. (It was fun watching it spin its wheels.)

The locations

I’ve timestamped each segment to the event video, and linked to the Apple Store where relevant. For non-Apple Store locations, I’ve linked to a reference site.

I’m about 99% confident in my results. If I got something wrong (or somehow missed a location), please let me know! I’m on Mastodon (preferred) and Bluesky, or you can email me.

On to the locations!

Flyovers

These are beauty shots, no Apple presenters. All are from the first few minutes and are on-screen for just a second or two; you can watch straight through from 1:17 until Tim Cook starts to speak.

- 1:17 - Pudong, China

- 1:18 - Al Maryah Island, Abu Dhabi

- 1:20 - Fifth Avenue, New York

- 1:21 - Marina Bay Sands, Singapore

- 1:22 - Central World, Bangkok

- 1:23 - Zorlu Center, Istanbul

- 1:25 - Pudong, China (again)

- 1:26 - Apple Park, Cupertino

Apple Stores

These are locations with an Apple presenter. I’ve included the person and their segment.

- 4:50 - Union Square, San Francisco (Kate Bergeron, AirPods Pro 3)

- 17:26 - Apple Park Visitor Center, Cupertino (rear; Stan Ng, Apple Watch)

- 19:12 - Apple Park Visitor Center, Cupertino (upper pavilion; Dr. Sumbul Ahmad Desai, Health)

- 23:04 - Apple Park Visitor Center, Cupertino (rear side; Amanda Santangelo, Apple Watch SE)

- 31:11 - Aventura, Florida (Kaiann Drance, iPhone 17)

- 42:56 - Michigan Avenue, Chicago (John Ternus, iPhone Air)

- 56:54 - Downtown Brooklyn, New York (Joz, iPhone 17 Pro)

Apple Park

Spots in and around Apple Park, Cupertino with an Apple presenter. I’ve included the person and their segment.

- 1:30 - Transit Center, Entrance 2 (Tim Cook, intro)

- 9:42 - Fitness Center (Julz Arney, AirPods Pro 3 fitness)

- 12:55 - Steve Jobs Theater (Tim Cook, Apple Watch intro)

- 29:16 - The Observatory (facing in; Tim Cook, iPhone 17 intro)

- 40:20, 53:48 - The Observatory (facing out; Tim Cook, iPhone Air and iPhone 17 Pro intros)

- 1:10:34 - Steve Jobs Theater (Tim Cook, outro)

Non-Apple Locations

Locations with an Apple presenter. I’ve included the person and their segment.

- 25:29 - Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve, CA (Eugene Kim, Apple Watch Ultra)

- 35:43 - Miami Beach, FL (Megan Nash, iPhone 17 cameras)

- 44:52 - BP Pedestrian Bridge at Millennium Park, Chicago (Tim Millet, iPhone Air’s Apple silicon)

- 1:01:37 - FDR Four Freedoms State Park, New York City/Roosevelt Island (Patrick Carroll, iPhone 17 Pro camera)

Final thoughts

To wrap this up, some thoughts on the Visitor Center, using ChatGPT, the one spot I can’t confidently pin down, and a brief note of thanks for a couple of the tools I used to put this together .

Staging Apple Park Visitor Center

This section caught my attention. Behind Stan Ng you can see product tables, a product wall, and a Genius-like bar with stools. None of that is normally there: that section of the store usually holds an Augmented Reality model of Apple Park and has a blank back wall. At first I thought it was a composite shot, but you can see the depth of the (physical) shelves at 23:04. The space was completely redressed just for this video.

ChatGPT

I’d rate ChatGPT’s performance highly, but when it failed, it failed hard. There are plenty of juicy nuggets in those failures, but in the interest of space, I’ll limit it to a few highlights:

- It initially identified Apple Al Maryah Island in Abu Dhabi as Apple Dubai Mall, stating confidently: “The golden carbon-fiber roof, the dramatic water features cascading down both sides of the approach, and the positioning between the two massive hotel/office towers make it unmistakable. This store is famous for its kinetic ‘Solar Wings’ that open to provide shade and views of the Dubai Fountain. […] I’d put it at 95% confidence.” It assuredly noted that “The water-stepped plaza and the gold roof are signature features of Apple Dubai Mall.”

- It wrongly identified Apple Aventura in Florida as Apple BKC in Mumbai (“Here’s why this is unmistakable”, with a 100% confidence level); Apple Saket (“Here’s why Saket makes sense and BKC doesn’t”; confidence level 95%); Al Maryah Island (“Here’s why this is finally correct,” citing the “egg-shaped bollards lining the approach” which apparently are “unique to this location’s waterside plaza”, with 100% confidence); Central World (“it finally clicks” because of the “distinctive ‘lotus petal’ roof pattern”) with 100% confidence (“this time I triple-checked the architecture against Apple’s site photos”). It then cycled through Apple Tower Theatre, Bağdat Caddesi, Marina Bay Sands, Via del Corso, The Grove, Emaar Square Mall (it appears there’s no such store), Brickell City Centre, Omotesando, Jing’an, and Piazza Liberty, considering then dismissing each in turn, before finally settling on the right store. Quite the global tour.

- For Apple Downtown Brooklyn, it incorrectly guessed Tower Theatre (“wait no, wrong coast”), Williamsburg, Upper East Side, landing eventually on the right store, but the wrong address. When I pointed that out, it spiraled, again guessing Williamsburg, “Apple Upper West Side’s little sibling” (what?), a couple of seemingly nonexistent stores (“The triangular plan, diagonal steel supports, and the elevated plaza setting are unmistakable: this is Apple Store, Washington Heights” and Pittsburgh/Carnegie Mellon), before finally returning both the correct store and the correct address.

Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve